This year, the Royal Entomological Society’s biennial symposium was held at Trinity College, Dublin (September 2nd-4th). This was the first time that the Society has held its symposium meeting outside the UK. The symposium theme this year was Insect Ecosystem Services, whilst the Annual Meeting which ran alongside the symposium meeting this year, was divided into nine themes, Biocontrol, Conservation, Decomposition, Insect Diversity and Services, Multiple Ecosystem Services, Outreach, Plant-Insect Interactions, Pollination and just in case anyone was feeling left out, Open.

The meeting convenors, Archie Murchie, Jane Stout, Olaf Schmidt, Stephen Jess, Brian Nelson, and Catherine Bertrand, came from both sides of the border so that the whole of Ireland was represented.

As a number of us were going from Harper Adams University we decided to use the Sail-rail option (any mainline station in the UK to Dublin for £78 return). We were thus able to feel smug on two levels, economically and ecologically 🙂 We set out on the morning of Tuesday 1st September from Stafford Railway Station, changing at Crewe for the longer journey to Holyhead.

Andy Cherrill, Tom Pope, Joe Roberts, Charlotte Rowley and Fran Sconce look after the luggage.

Just over two hours later we arrived at Holyhead to join the queue for the ferry to Dublin.

In the queue at Holyhead.

Two of my former students were supposed to join us on the ferry but due to a broken down train, only one of them made it in time, Mark Ramsden being the last passenger to board whilst Mike Garratt had to wait for the next ferry.

Tom Pope and Mark Ramsden relaxing on board the ferry.

We arrived at Trinity College in the pouring rain, but still got a feel for some of the impressive architecture on campus.

I never quite worked out what this piece of art was about, although the added extra made me smile.

The bedrooms were very self-contained – the bed was rather neatly built into the storage although it did make me feel like I was sleeping on a shelf.

After settling in we found a pleasant pub and sampled some of the local beverages.

Despite the beverage intake, I was up bright and early on Wednesday morning, in fact so early, that I was not only first at the Registration Desk, but beat the Royal Entomological Society Staff there.

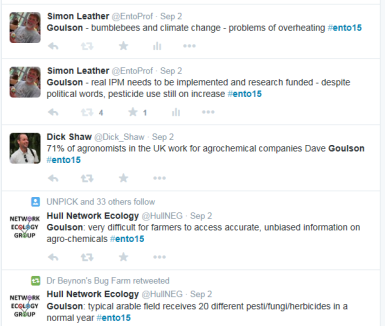

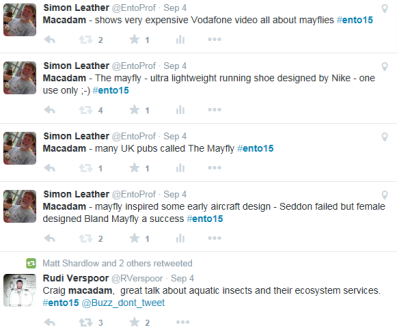

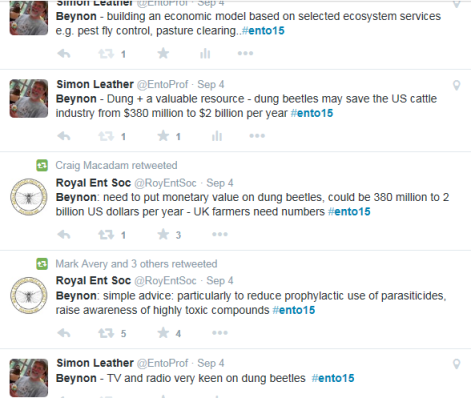

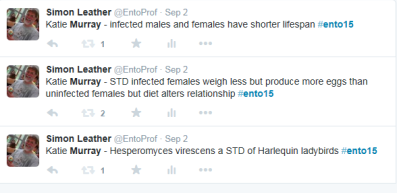

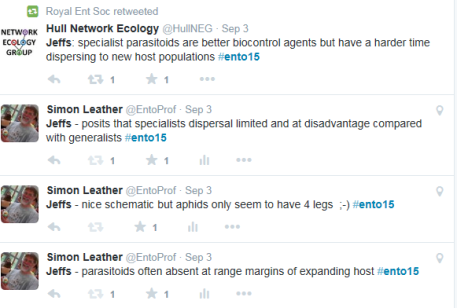

After setting up our stand we were able to enjoy the programme of excellent plenary talks and those in the National Meeting themes. There was a great deal of live tweeting taking place so I thought I would give you a flavour of those rather than describing the talks in detail. For the full conference experience use Twitter #ento15

Dave Goulson from Sussex University, was the first of the plenary speakers and lead off with a thought-provoking talk about the global threats to insect pollination services.

I was a bit disappointed that John Pickett, who was chairing the session cut short a possibly lively debate between Lin Field and Dave Goulson about pesticide usage.

The next plenary speaker was Akexandra-Maria Klein from Freiburg speaking about biodiversity and pollination services.

The third plenary speaker was Lynn Dicks from Cambridge asking how much flower-rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators?

I was the fourth plenary speaker, talking about how entomology and entomologist have influenced the world. I deliberately avoided crop protection and pollination services.

I was very pleased that my talk was on the first day as this allowed me to enjoy the rest of the meeting, including the social events to the full.

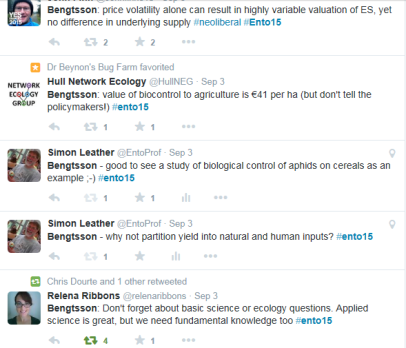

The following day, Jan Bengtsson from SLU in Sweden spoke about biological ontrol in a landscape context and the pros and cons of valuing ecosystem services.

Jan was followed by Sarina Macfadyne from CSIRO, Australia, who spoke about temporal patterns in plant growth and pest populations across agricultural landscapes and astounded us with the list of pesticides that are still able to be used by farmers in Australia.

The next plenary speaker, Charles Midega – icipe spoke about the use of companion cropping for sustainable pest management in Africa and extolled the virtues of ‘push-pull’ agriculture.

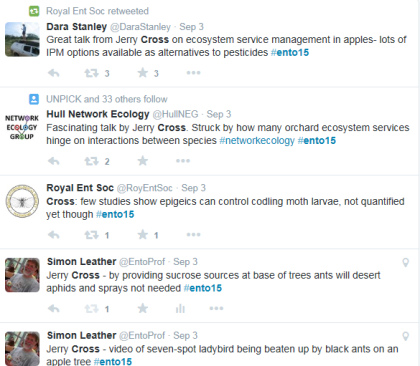

The last plenary of Day Two was Jerry Cross of East Malling Research who enlightened us about the arthropod ecosystem services in apple orchards and their economic benefits. He also highlighted the problems faced by organic growers trying to produce ‘perfect’ fruit for the supermarkets.

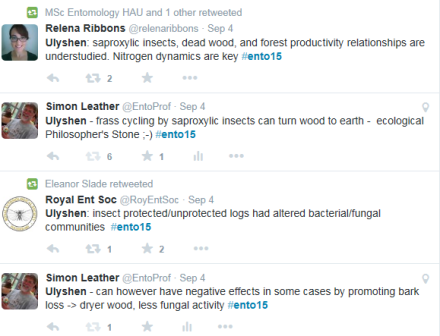

The third day of the conference plenaries was kicked off by Michael Ulyshen from the USDA Forest Service – who reviewed the role of insects in wood decomposition and nutrient cycling. My take-home image form his talk was the picture of how a box of woodchips was converted to soil by a stage beetle larvae completing its life cycle.

The last plenary of the morning was Craig Macadam from BugLife who explained to us that aquatic insects are much than just fish food and play cultural role as well as an ecological one.

The afternoon session of the last day was Sarah Beynon, the Queen of Dung Beetles who enthralled us with her stories of research and outreach . It was a testament to the interest people had in what Sarah had to say, that the audience was till well over a hundred, despite it being the last afternoon.

The final plenary lecture, and last lecture of the conference, was given by Tom Bolger from the other university in Dublin, UCD. Hi subject was soil organisms and their role in agricultural productivity.

I know that I have only given you a minimal survey of the plenary lectures, but you can access the written text of all the talks in the special issue of Ecological Entomology for free.

I did of course attend a number of the other talks, and had to miss many that I wanted to see but which clashed with the ones that I did see.

Eugenie Regan gave a great talk on her dream of setting up a Global Butterfly Index.

One of my PhD students, Joe Roberts, gave an excellent talk on his first year of research into developing an artificial diet for predatory mites.

Katie Murray, a fomer MREs student of mine, now doing a PhD at the University of Stirling, gave a lively talk on Harlequin ladybirds and the problems they may be having with STDs.

Rudi Verspoor, yet another former MRes student gave us an overview of a project that he and Laura Riggi, have developed on entomophagy in Benin.

Peter Smithers from Plymouth University gave an amusing and revelatory talk the ways in which Insects are perceived and portrayed. Some excellent material for my planned book on influential entomology 😉

Chris Jeffs, yet another former MRes student gave an excellent presentation about climate warming and host-parasitoid interactions.

My colleague (and former MSc student) Tom Pope bravely volunteered to step into a gap in the programme and gave an excellent talk about how understanding vine weevil behaviour can help improve biological control programmes.

Jasmine Parkinson from the University of Sussex, and incidentally a student of a former student of mine, gave an excellent and well-timed talk about mealybugs and their symbionts.

Charlotte Rowley from Harper Adams gave an excellent talk about saddle-gall midge pheromones.

Another former student, Mike Garratt, now at Reading University, gave an overview of his work on hedgerows and their dual roles as habitats for pollinators and natural enemies.

There were also excellent talks by Jessica Scrivens on niche partitioning in cryptic bumblebees, Relena Ribbons on ants and their roles as ecological indicators, Rosalind Shaw on biodiversity and multiple services in farmland from David George on how to convince farmers and growers that field margins are a worthwhile investment. My apologies to all those whose talks I missed, I wanted to see them but parallel sessions got in the way.

Richard Comont, whose talk I missed, very recognisable from the back 😉

I leave you with a selection of photographs from the social parts of the programme including our last morning in Dublin before catching the ferry home on Saturday morning.

The Conference Dinner – former and current students gathering.

Tom Pope signs the Obligations Book – his signature now joins those of Darwin and Wallace.

Archie Murchie with RES Librarian Val McAtear.

The youngest delegate and his father; I hope to see him at Harper Adams learning entomology in the near future.

Entomologists learning how to dance a ceilidh.

Moving much too fast for my camera to capture them.

Academic toilets – note the shelf on which books can be placed whilst hands are otherwise occupied.

On site history.

Impressive doorway in the Museum café.

The Natural History Museum was very vertebrate biased.

They certainly didn’t way know the best way to mount aphids.

I was, however, pleased to see a historical Pooter.

On our final day the sun actually made an appearance so our farewell to Ireland was stunning.

And finally, many thanks to the conference organizers and the Royal Entomological Society for giving us such a good experience. A lot to live up to for ENTO’16 which will be at Harper Adams University. We hope to see you there.

Postscript

As a result of being tourists on Saturday morning we were exposed to a lot of gift shops and in one I impulsively bought a souvenir 😉