In a very early post I mentioned that one of the reasons that I love aphids so much is their life-cycles https://simonleather.wordpress.com/aphidology/ and the fantastic jargon that is used to describe them. Many undergraduates find the jargon off-putting but it was this complexity that really grabbed my imagination.

Insects are probably the most diverse group of organisms on Earth (Grimaldi & Engel, 2005) and their life cycles range from simple sexual and asexual styles to complex life cycles encompassing obligate and facultative alternation of sexual and asexual components. Nancy Moran (1992) suggests that in the insect world probably the most intricate and varied life cycles are found in aphids and I certainly wouldn’t disagree.

There are basically two types of aphid life-cycles, non-host alternating (autoecious, monoecious) and host alternating (heteroecious). Autoecious aphids spend their entire life cycle in association with one plant species as shown below (Dixon, 1985).

(or group of related plant species), whereas heteroecious aphids divide their time between two very different species of host plant, usually a tree species (the primary host) on which they overwinter, and an herbaceous plant species (the secondary host) on which they spend their summer.

Approximately 10% of aphid species are heteroecious. The ancestral aphid life cycle is thought to have been winged, egg laying and autoecious on a woody host plant almost certainly conifers and the oldest families of woody angiosperms e.g. Salicaceae (Mordwilko, 1928; Moran, 1992).

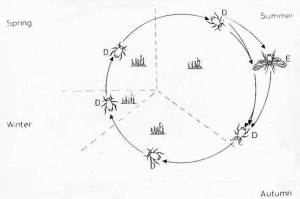

Aphid life cycles can also be described as holocyclic, in which cyclical parthenogenesis occurs, with aphids reproducing sexually in the autumn to produce an overwintering egg, in temperate regions and parthenogenetically during spring and summer as shown below for the sycamore aphid (Dixon, 1985).

Some aphids are anholocyclic where the clone is entirely asexual reproducing by parthenogenesis throughout the year. This is often seen in locations where winter conditions are mild, in the tropics for example or as a bit of an oddity around hot-springs in Iceland.

Parthenogenesis in aphids is coupled with live births and reduced generation times through the phenomenon of telescoping generations. Parthenogenesis in aphids developed early on but whether the oldest aphids (200 mya) were parthenogenetic is not known.

Host alternation appears to have arisen more than once (Moran, 1988), and occurs in four slightly different forms depending on the taxon in which it occurs. The main differences being in whether the sexual forms are produced on the primary (winter) host (the host on which the eggs are laid), or as in the case of the Aphidini, the males being produced on the secondary (summer) host and the sexual females produced on the primary host. The majority of aphids host alternate between unrelated woody and perennial hosts, but some species host alternate between herbaceous plants e.g. pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum alternates between the perennial vetches and the annual peas Pisum sativum (Muller & Steiner, 1985) and Urleucon gravicorne alternates between the perennial Solidago and the annual Erigeron (Moran 1983). Some aphid species such as Rhopalosipum padi, have clones that are holocyclic and some that are anholocyclic, so hedge their bets and also gives me the opportunity to slip in a great slide kindly lent to me by my friend Richard Harrington at Rothamsted Research.

One of the things that is rather puzzling is why some aphid species should have adopted a host alternating life cycle which on the face of it, seems to be rather a risky strategy. You could liken it to looking for a needle in a hay-stack; only about 1 in 300 aphids that leave the secondary host at the end of summer are likely to find their primary host (Ward et al, 1998). There are a number of theories as to why it has evolved.

1. The nutritional optimization through complementary host growth hypothesis states that heteroecy has been favoured by natural selection because it enables a high rate of nutrient intake throughout the season (Davidson, 1927; Dixon, 1971). In essence, the clone moves from a host plant where food quality is low and moves onto a herbaceous host that is growing rapidly and thus provides a good source of nutrition. In autumn, the clone moves back to its primary woody host where leaves are beginning to senesce and provide a better source of nutrition as seen below (Dixon, 1985).

On the other hand, non-host alternating aphids such as the sycamore aphid, Drepanosiphum platanoidis, or the maple aphid, Periphyllus testudinaceus, reduce their metabolism and tough it out over the summer months when the leaves of their tree hosts are nutritionally poor, the former as adults, the latter as nymphs (aphid immature forms) known as dimorphs. Mortality over the summer in these species is, however, very high. In some years I have recorded almost 100% mortality on some of my study trees, so very similar to the 99.4% mortality seen in the autumn migrants (gynoparae) of the bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhoaplosiphum padi. Other autoecious aphids are able to track resources if they live on host plants that continue to develop growing points throughout the summer.

Verdict: No apparent advantage gained

2. The oviposition site advantage hypothesis states that primary woody hosts provide better egg laying sites and provide emerging spring aphids with guaranteed food source (Moran, 1983). There is however, no evidence that eggs laid on woody hosts survive the winter better than those laid in the herbaceous layer. Egg mortality in both situations ranges from 70-90% (Leather, 1983, 1992, 1993).

Verdict: No apparent advantage gained

3. The enemy escape hypothesis states that by leaving the primary host as natural enemy populations begin to build up and moving to a secondary host largely devoid of enemies confers an advantage on those species that exhibit this trait (Way & Banks, 1968). At the end of summer, when the natural enemies have ‘found’ the clone again, the clone then migrates back to its primary host, which theoretically is now free of natural enemies. This is an attractive idea as it is well known that natural enemies tend to lag behind the populations of their prey.

Verdict: Possible advantage gained

4. The Rendez-vous hosts hypothesis suggests that host alternation assists mate location and enables wider mixing of genes than autoecy (Ward, 1991; Ward et al. 1998). This seems reasonable, but as far as I know, no-one has as yet demonstrated that host-alternating aphid species have a more diverse set of genotypes than non-host alternating aphids.

Verdict: Not proven

5. The temperature tolerance constraints hypothesis which postulates that seasonal morphs are adapted to lower or higher temperatures and that they are unable to exist on the respective host plants at the ‘wrong time of year’ (Dixon, 1985). I don’t actually buy this one at all, as I have reared spring and autumn morphs at atypical temperatures and they have done perfectly well (Leather & Dixon, 1981), the constraint being the phenological stage of their host plant rather than the temperature. In addition, there are some host alternating aphid species in which the fundatrix can exist on both the secondary and primary hosts (if the eggs are placed on the secondary host). This has been experimentally demonstrated in the following species:

Aphis fabae Spindle & bean Dixon & Dharma (1980)

Cavariella aegopdii

Cavariella pastinacea Willows and Umbelliferae Kundu & Dixon (1995)

Cavariella theobaldi

Metopolophium dirhodum Rose and grasses Thornback (1993)

Myzus persicae Prunus spp & 40 different plants Blackman & Devonshire (1978)

Verdict: Unlikely

6. The escape from induced host-plant defences hypothesis (Williams & Whitham, 1986), which states that by leaving the primary host as summer approaches, the aphids escape the plant defences being mustered against them. This is only really applicable to those gall aphids where galled leaves are dropped prematurely by the host plant.

Verdict: Special case pleading?

7. The constraint of fundatrix specialisation hypothesis is that of Moran (1988), who argues that heteroecy is not an optimal life cycle but that it exists because the fundatrix generation (the first generation that hatches from the egg in spring) on the ancestral winter host, are constrained by their host affinities and are unable to shift to newly available nutritionally superior hosts. Whilst it is true that some host alternating aphids are however, very host specific as fundatrcies, some aphids are equally host-specific as oviparae at the end of the year the constraints of ovipara specialisation

For example, in the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiophum padi, the fundatrices are unable to feed on senescent leaf tissue of the primary host, their offspring can only develop very slowly on ungalled tissue and all their offspring are winged emigrants (the alate morph that flies from the primary host to the secondary host) (Leather & Dixon, 1981). The emigrants are able to feed as nymphs on the primary host on which they develop and as adults on their secondary host, but not vice versa (Leather et al., 1983). The autumn remigrants (gynoparae, the winged parthenogenetic females that fly from the secondary hosts to the primary hosts on the other hand, feed on the secondary host as nymphs but are unable to feed on the primary host as adults (Leather, 1982; Walters et al., 1984). The black bean aphid shows similar, but less rigid host specificity and whilst there is a distinct preference for the relevant host plant (Hardie et al., 1989), parthenogenetic forms can occur throughout the summer on the primary host (Way & Banks, 1968), particularly if new growth is stimulated by pruning (Dixon & Dharma, 1980). There are also at least two examples of where both the primary and secondary host are herbaceous (see earlier). In both these cases the fundatrices could exist on both the primary and secondary host plants

Verdict: Not proven

So what do I think? For years I was very firmly convinced that the nutritional optimization hypothesis was the obvious answer; after all Tony Dixon was my PhD supervisor 😉 Now, however, having lectured on the subject to several cohorts of students, if I was forced to pick a favourite from the list above, I would do a bit of fence-sitting and suggest a combination of the nutritional optimization and enemy escape hypotheses. What do you think? There are cetainly a number of possible research projects that would be interesting to follow up, the problem is finding the funding 😦

Sources

Blackman, R.L. & Devonshire, A.L. (1978) Further studies on the genetics of the carboxylase-esterase regulatory system involved in resistance to orgaophosphorous insecticides in Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Pesticide Science 9, 517-521

Davidson, J. (1927) The biological and ecological aspects of migration in aphids. Scientific Progress, 21, 641-658

Dixon, A.F.G. (1971) The life cycle and host preferences of the bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi (L) and its bearing on the theory of host alternation in aphids. Annals of Applied Biology, 68, 135-147. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1971.tb06450.x/abstract

Dixon, A.F.G. (1985) Aphid Ecology Blackie, London.

Dixon, A.F.G. & Dharma, T.R. (1980) Number of ovarioles and fecundity in the black bean aphid, Aphis fabae. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 28, 1-14. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1980.tb02981.x/abstract?deniedAccessCustomisedMessage=&userIsAuthenticated=true

Grimaldi. D. & Engel, M.S. (2005) Evolution of the Insects, Cambridge University Press, New York

Hardie, J. (1981) Juvenile hormone and photoperiodically controlled polymorphism in Aphis fabae: postnatal effects on presumptive gynoparae. Journal of Insect Physiology, 27, 347-352.

Hardie, J. Poppy, G.M. & David, C.T. (1989) Visual responses of flying aphids and their chemical modification. Physiological Entomology, 14, 41-51. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1989.tb00935.x/abstract

Kundu, R. & Dixon, A.F.G. (1995) Evolution of complex life cycles in aphids. Journal of Animal Ecology, 64, 245-255. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/5759?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21102533364873

Leather, S.R. (1982) Do gynoparae and males need to feed ? An attempt to allocate resources in the bird cherry-oat oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 31, 386-390. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1982.tb03165.x/abstract

Leather, S.R. (1983) Forecasting aphid outbreaks using winter egg counts: an assessment of its feasibility and an example of its application. Zeitschrift fur Angewandte Entomolgie, 96, 282-287. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0418.1983.tb03670.x/abstract

Leather, S.R. (1992) Aspects of aphid overwintering (Homoptera: Aphidinea: Aphididae). Entomologia Generalis, 17, 101-113. http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/19941101996.html;jsessionid=60EA025C7230C413B6094BCC4966EC06

Leather, S.R. (1993) Overwintering in six arable aphid pests: a review with particular relevance to pest management. Journal of Applied Entomology, 116, 217-233. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0418.1993.tb01192.x/abstract?deniedAccessCustomisedMessage=&userIsAuthenticated=true

Leather, S.R. & Dixon, A.F.G. (1981) Growth, survival and reproduction of the bird-cherry aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi, on it’s primary host. Annals of applied Biology, 99, 115-118. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1981.tb05136.x/abstract

Moran, N.A. (1983) Seasonal shifts in host usage in Uroleucon gravicorne (Homoptera:Aphididae) and implications for the evolution of host alternation in aphids. Ecological Entomology, 8, 371-382. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1983.tb00517.x/full

Moran, N.A. (1988) The evolution of host-plant alternation in aphids: evidence for specialization as a dead end. American Naturalist, 132, 681-706. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/2461929?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21102533364873

Moran, N.A. (1992) The evolution of aphid life cycles. Annual Review of Entomology, 37, 321-348. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.001541

Mordwilko, A. (1928) The evolution of cycles and the origin of heteroecy (migrations) in plant-lice. Annals and Magazine of Natural History Series 10, 2, 570-582

Muller, F.P. & Steiner, H. (1985) Das Problem Acyrthosiphom pisum (Homoptera: Aphididae). Zietsschrift fur angewandte Entomolgie 72, 317-334

Thornback, N. (1983) The Factors Determiining the Abundance of Metopolophium dirhodum (Walk.) the Rose Grain Aphid. PhD Thesis, University of East Anglia.

Walters, K.F.A., Dixon, A.F.G., & Eagles, G. (1984) Non-feeding by adult gynoparae of Rhopalosiphum padi and its bearing on the limiting resource in the production of sexual females in host alternating aphids. Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 36, 9-12. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1984.tb03398.x/abstract?deniedAccessCustomisedMessage=&userIsAuthenticated=true

Ward, S.A. (1991). Reproduction and host selection by aphids: the importance of ‘rendevous’ hosts. In Reproductive Behaviour of Insects: Individuals and Populations (eds W.J. Bailey & J. Ridsdill-Smith), pp 202-226. Chapman & Hall, London.

Ward, S.A., Leather, S.R., Pickup, J., & Harrington, R. (1998) Mortality during dispersal and the cost of host-specificity in parasites: how many aphids find hosts? Journal of Animal Ecology, 67, 763-773. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2656.1998.00238.x/full

Way, M.J. & Banks, C.J. (1968) Population studies on the active stages of the black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scop., on its winter host Euonymus europaeus L. Annals of Applied Biology, 62, 177-197. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1968.tb02815.x/abstract

Williams, A.G. & Whitham, T.G. (1986) Premature leaf abscission: an induced plant defense against gall aphids. Ecology, 67, 1619-1627. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1939093?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21102533364873

Fantastic food for thought! A great summary and really enjoyable read.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Winter’s Tale – aphid overwintering | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Not all aphids have wings | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Mellow Yellow – Not all aphids live on green leaves | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Just came across this great post while googling “heteroecy” (revealing my ignorance) and thought I should update it with this cool new paper:

Hardy, N. B., Peterson, D. A., & Dohlen, C. D. (2015). The evolution of life cycle complexity in aphids: ecological optimization, or historical constraint?. Evolution. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/evo.12643/epdf

Thanks for helping me put their results into context : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and the link to the paper

LikeLike

Pingback: Not all aphids get lost | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Red, green or gold? Autumn colours and aphid host choice | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Not all aphid galls are the same | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: The bane of PhD students– the General Discussion | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Not all aphids get eaten – “bottom-up” wins this time | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: The Roundabout Review 2018 | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Ten more papers that shook my world – complex plant architecture provides more niches for insects – Lawton & Schroeder (1977) | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: The Roundabout Review 2019 – navel gazing again | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: On rarity, apparency and the indisputable fact that most aphids are not pests | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Opening and closing windows for herbivorous insects – Ten more papers that shook my world (Feeny, 1970) | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Booze, sweat and blood – the birth of a paper | Don't Forget the Roundabouts