Today I turned 60 – an event which has come as a bit of a surprise to me as inside I still feel about 17 😉 I thought, given the occasion and the fine example set by Jeff Ollerton‘s recent birthday blog post that it seems a good time to reflect on my career in particular and academic careers in general. Despite there already being at least two other excellent articles about the “Seven Ages”, Jerry Coyne’s, The Seven Ages of the Scientist and Athene Donald’s The Seven Ages of an Academic Scientist, I felt no qualms in adding my own modest contribution to the genre 😉

Given my own career trajectory it turns out that I need more than seven ages, so as an entomologist I feel justified in adding five larval or nymphal instars to the traditional progression.

The Larval Stages

The Infant (first instar)

According to Shakespeare “mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms”, which spending the early part of my childhood in colonial Ghana is actually very apt,

although the photograph below shows a very contented baby indeed.

I have no entomological memories from this time, although given that then it was normal practice to leave babies outside in their prams, I am sure that I was exposed to the whole range of flying Ghanaian insects. There is some evidence of an early interest in nature and entomology in the picture below where I seem to be investigating a small white butterfly whilst indulging in some early forestry work.

My first real biological memory, is however, non-entomological, the blue whale skeleton in the Natural History Museum London in 1958 when my parents were on home leave.

The Schoolboy (second instar)

In 1960 my father was moved to Jamaica to work in the Department of Agriculture as a Plant Pathologist and this is where I started my formal education. Shakespeare describes the schoolboy as “whining schoolboy with his satchel, and shining morning face, creeping like a snail unwillingly to school”.

I certainly had a satchel and it is from this period of my life that I have my first definite entomological memories. We lived in a suburb of Kingston, 32 Gardenia Avenue in Mona Heights. My father kept bees and I spent a lot of time playing with ants, conducting behavioural experiments with crab spiders and having close encounters with wasps and apparently in this picture from 1961, helping with my father’s very luxuriant garden; he grew a great variety of ornamental plants as well as fruit and

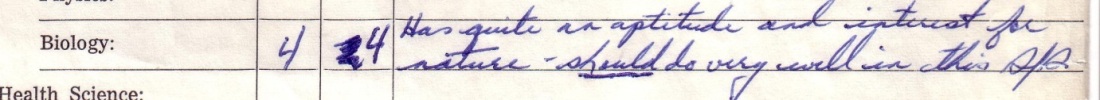

vegetables, including grapes, bananas, passion fruit, papayas, peanuts and breadfruit as well as coffee and more traditional vegetables. My final school report from my time in Jamaica shows a prescient comment from my biology teacher;

Secondary school (third instar)

My father’s next posting was to Hong Kong to work for the Ministry of Agriculture; his office was in the New Territories but we lived in Kowloon (Wylie Gardens) where I attended King George V School. Biology was again my favourite subject but apart from cockroaches and ants my entomological experiences were very limited.

Keeping my mouth shut to hide my orthodontic appliances 1968.

Boarding school (fourth instar)

In 1968 my father returned briefly to the UK before his next posting to Fiji and I was sent to a state school, Ripon Grammar School, which had a boarding section. I was to spend five relatively happy years there and despite the competing interests of girls and sports, further developed my interest in invertebrate zoology, due in the main part to my zoology teacher ‘Brian’ Ford. I have many happy memories of pond dipping, searching for Cepea nemoralis and generally fossicking around in hedgerows.

When on school holidays in Fiji I found time to investigate the local insect and amphibian fauna; our house seemed to attract toads in huge numbers which my brothers and I used to competitively collect in buckets for later release.

Sixth form (final instar)

In my two final years at school sport and girls continued to play a larger part in my life than entomology although I see from the fly-leaf of my books from that time that I owned and had read both volumes of Ralph Bucshbaum’s Life of the Invertebrates and also Darwin’s Origins.

Ripon Grammar School 2nd XV – I am third from the left on the front row.

Careers advice when I was at school was not very sophisticated and if you did Biology ‘A’ Level and were a school prefect, it was automatically taken that you were either destined to be a Doctor, a Vet or a Dentist.

I was no different and despite my misgivings, duly applied for and was accepted at Birmingham University to read Medicine. As luck would have it, things did not work out as planned and after a less than happy year at Aston University in Birmingham, in 1974 I left Birmingham and moulted into a proto-entomologist at the University of Leeds.

The Undergraduate

The discovery that learning can be fun and that there might actually be a career in doing something that you enjoy.

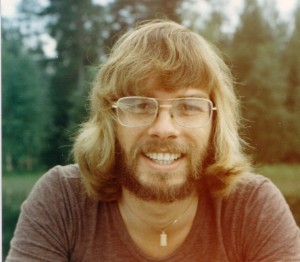

I did a now extinct degree (although I have plans to exhume it), Agricultural Zoology, essentially a year of vertebrate zoology, with two years of invertebrate zoology, essentially applied entomology, parasitology and nematology. I loved it and thrived on it and grew my hair even longer.

I decided to become an entomologist in my second year and discovered the wonders of aphids at the same time. It was also round about this time that I decided I was going to become a university academic and started to work a lot harder; the logical end point of someone with a mother who was a secondary school biology teacher and a father who was a research scientist.

The Postgraduate

Discovering that being on “the road to find out” (Cat Stevens) is exhilarating

I did my PhD at the University of East Anglia in Norwich – Aspects of the Ecology of the Ecology of the Bird Cherry Aphid, under the supervision of Professor Tony Dixon. A totally fantastic time, despite the ‘second year blues’ which all PhD students seem to go through when they think that they don’t have enough data. I was lucky enough to be in a large research group, at one stage there were thirteen of us in the lab, so there was always plenty of help and advice available. In addition we had the excitement of conferences and the first unsteady steps towards learning to lecture, mainly demonstrating in undergraduate practicals; I spent a lot of time pithing frogs for physiology classes (don’t ask) and also tutoring first year students in mathematics. We also played a lot of squash and enjoyed our social life; for those of you who know Norwich, The Mitre pub on Earlham Road, was our regular haunt.

The post-doc

Discovering how to run a research lab

I did two brief post-docs, the first in Finland, under the auspices of the Royal Society and the

second back at the University of East Anglia funded by the Agriculture and Food Research Council, both working on cereal aphids. At this stage of my career I started to learn how to supervise postgraduate students; the first port of call in a busy lab after the senior PhD student has failed to supply an answer is always the post-doc as the lab head is inevitably very busy. I also got my first real opportunity to lecture undergraduates, which turned out to be a lot harder than I had thought it would be even when talking about my own research.

Interlude or host alternation

The Research Scientist

Discovering that directed research on its own is not enough

In a normal academic career, the next stage after post-doc is an appointment as a University Lecturer. In the early 1980s university lectureships were in short supply and many of us who would normally have gone into an academic career found ourselves either having to go abroad as lecturers at Commonwealth universities (I was offered but turned down a lectureship at Kano University in Nigeria) or joining research institutes. In 1982 I joined the UK Forestry Commission’s Northern Research Station where I spent ten years as a forest entomologist, answering enquiries, conducting directed research and giving the occasional guest lecture. I was however, lucky enough to be able to gain some PhD supervisory experience and after ten years, the last five which were increasingly frustrating, was lucky enough in 1992 to be appointed to a Lectureship at the Silwood Park campus of Imperial College. In retrospect this was the last time I was able to spend about 90% of my time at the bench and in the field doing ‘hands on’ research, but I have never regretted moving into academia – the opportunity of being able to pass on what you have discovered and hopefully enthuse and motivate a new generation more than makes up for the loss.

Back to the primary host

The Lecturer

When I discover that I love teaching

You may have noticed that I have had a haircut; it was a source of some amusement to me that on joining the university sector I was expected to get my hair cut.

I was appointed as a Lecturer in Pest Management to teach on the world-renowned MSc Entomology course at Silwood Park, and as I was replacing a specific person (Geoff Norton), although not in exactly the same subject area, my ‘grace’ period was shorter that it might have been. Normally at research intensive institutions like Imperial College, new appointments are given two to three years to apply for grants and get their research groups started before being given teaching and departmental jobs. I had a year, but as I discovered that I very much enjoyed teaching (something that many of my colleagues then and later found very strange) I was not dismayed. Unlike some of my colleagues I had read the dictionary definition of the word lecturer: noun. One who delivers lectures, especially professionally. I have never really understood the mentality of those who aspire to university positions and yet find the idea of having to teach students not only a distraction but in some cases abhorrent and to be avoided at all costs and strive to obtain funding to buy them out of teaching as soon as possible. Some of my senior colleagues at Imperial College (and elsewhere) had and have almost no experience of teaching at all and so have no idea of what is involved in delivering a decent course, a state of affairs that explains some of the very strange decisions that are made at some of the research intensive universities in the UK. I often felt that they would be much happier in a research institute.

I also discovered that if you take teaching seriously then your ‘bench time’ is much reduced and you begin your career as a research manager, appointing PhD students and post-docs to carry your research ideas forward. I made a decision early on that I would attempt to keep some of my skills extant and set up a long-term field project looking at the insect communities living on sycamores at Silwood Park, especially the aphids. This meant that I had to set a day a week aside to collect data. By doing this it meant that I had a reality check on what was actually possible. I have seen too many colleagues who because of the time they had spent away from the bench or the field, had totally unrealistic expectations of what was actually possible to be achieved by their students and research assistants.

The Senior Lecturer

When the Department discovers that I love teaching

In 1996 I was promoted to Senior Lecturer (I think that it is a real shame that some UK universities have decided to adopt North American terminology and introduce the title of Associate Professor, apparently to avoid confusing the rest of the World. At Imperial College promotion to Senior Lecturer was to reward teaching excellence and was usually the kiss of death for any further promotion.

Senior Lecturer in Applied Ecology

I was as well as teaching on the MSc Entomology course doing an increasing amount of undergraduate teaching including a final year course in Applied Ecology of which I was very proud, hence the decision to retitle myself. I was also very busy with external activities, being on the Editorial Board of the Bulletin of Entomological Research and just been appointed as Editor-in-Chief of Ecological Entomology, just finished a term on the council of the Royal Entomological Society and been appointed to a slew of Departmental and University committees. My research group was really starting to take off, I was supervising 8 PhD students at the time; given the poor return rate on major grant applications in the UK, I decided early on that going for PhDs was a better use of my limited time and this is a strategy that I have mainly followed to the present day.

This does not include MSc or BSc students – they would add about 10 to each yearly figure from 1995 onwards

The Reader

When I discover that it is possible to get even busier

In 2002 I was promoted to Reader one of the definitions of which according to Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary is defined as follows; Old English rǣdere ‘interpreter of dreams, reader’. In the UK university system, it is the rank below full Professor and comes with an endowed title, in my case I chose to become Reader in Applied Ecology to reflect the

myriad teaching roles I had accumulated and also to encompass the fact that my research group no longer dealt solely with arthropods, vertebrates had somehow sneaked their way in. Looking at Athene Donald’s list I see that I was pretty much doing a professorial role, serving on external committees, validating degrees for other universities and acting as an external examiner. I was also appointed as Editor-in-Chief of Insect Conservation and Diversity, a new journal for the Royal Entomological Society. My administrative duties had also continued to increase. It was no wonder that my beard was getting greyer! I was however still preparing my own talks, although I will confess that a lot of my data analysis was being passed on to members of the group, duly acknowledged of course. I am extremely grateful that I have always had a loyal and very supportive research group, without their help life would have been impossible. My thanks to you all (if any of you are reading this).

The Professor

Discovering the joys of being pretty much able to do what I want (with certain restrictions)

It became increasingly obvious that things could not carry on as they were, my teaching and administrative loads were becoming ridiculous; our Director of Teaching calculated that I was actually doing more teaching than anyone else in the Department including the Teaching Fellows. I was seriously considering early retirement although I was reluctant to do this as I was sure that with my retirement the last entomology degree in the UK would quickly disappear. Luckily in 2012 my team and I were miraculously offered the chance to move to a new more supportive location, Harper Adams University in Shropshire.

So now I have become a Senior Professor, with a new entomology building, with less undergraduate teaching, which I miss, and a role that requires me to sit on more external and internal committees, to meet the great and the good and to make solemn pronouncements. At the same time however, it does allow me to plough my own furrow and to influence university policy. Most importantly I no longer feel that I am beating my head against a brick wall and that the future of entomology as a degree course in the UK is much safer than it was five years ago. I think I am at Stage 4 in Jerry Coyne’s list as I now find that I am much more interested in synthesizing and disseminating what I have learnt rather than doing original research – I can feel a book coming on 😉

My hope is that in five years time when I become a retired Professor and my hair and beard colour are the same, that entomology will be taught at more than one university in the UK and not just at postgraduate level.

A small point of personal satisfaction, is that, despite my elevation, I still do not own a suit 😉

For reference

Jerry A. Coyne’s summary, reproduced from his blog

- As student, listens to advisor give talk on student’s own work

- As postdoc, gives talks about his/her own work

- As professor, gives talks about his/her students’ work

- Talks and writes about “the state of the field”

- Talks and writes about “the state of the field” eccentrically and incorrectly—always in a self-aggrandizing way.

- Gives after-dinner speeches and writes about society and the history of the field

- Writes articles about science and religion

And the famous original from which the title is borrowed and adapted.

Seven Ages Of Man

(from As You Like It by William Shakespeare)

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players,

They have their exits and entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then, the whining schoolboy with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden, and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice

In fair round belly, with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws, and modern instances,

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose, and pouch on side,

His youthful hose well sav’d, a world too wide,

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again towards childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Great post Simon, and a very happy birthday to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy birthday. A very interesting post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks

LikeLike

Happy 60th dear Simon (albeit a few days late). Thank you for this delightful read!

LikeLike

Actually not late at all – today is the day – man thanks and good to hear from you again

LikeLike

A thoroughly enjoyable read. I think we are all exceedingly happy you decided to pursue entomology. I have to just add, you had quite the groovy hair back in the day. Wishing you a ento-tastic birthday!

LikeLiked by 1 person

many thanks – I did like my long hair 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

A really enjoyable post, thank you for sharing. I particularly enjoyed the part where you say ‘I have never regretted moving into academia – the opportunity of being able to pass on what you have discovered and hopefully enthuse and motivate a new generation’. But I also absolutely hope entomology receives more appreciation, especially with the increased public awareness of it’s beauty and value. Looking forward to reading your book! Hope you have a really lovely birthday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks

LikeLike

‘Fossicking’. What a fabulous word!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I enjoyed your seven ages. The “teaching bad”, “research good” dichotomy is encouraged by some Heads of Department despite the fact that the students pay the bills. I always enjoyed the mixture of teaching and research and I think I found ways of being innovative in both.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes it has always been my mission to try and make the best of both worlds – unfortunately not something Imperial as an organization bought into, although I was always assured by my HOD that I was very much appreciated, but not enough for him to do anything about it!

LikeLike

Happy Birthday as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy birthday – I’m impressed by your long hair!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very enjoyable read. I hope more entomology degrees will be offered in the future. My bro was an entomological inspiration to me but couldn’t get the grades for imperial. It’s a shame practical experience isn’t considered for admission. If bee decline has done anything, it’s brought awareness to the study of insects to the public.

The transition of positions you speak of was also insightful Simon. With the fees the way they are and a bottleneck of positions, my generation is feeling the pressure. Teaching lectureships seem non existent and even at Uppsala, i am alone in asking for teaching opportunities. All to often we add fuel to the stereotype of reclusive scientists. If only more scientific corridors were packed with professors like you, universities would be much happier places to work, with less depression. Although green tea would be contraband and wine would no longer be kept in the emergency draw 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks Rosie and we can only hope that more universities began to take on board that teaching is as equally important as research and that an equitable balance needs to be struck – it would also hope if the way in which universities were assessed and funded was revisited

LikeLike

Happy Birthday! Teachers are very special people they will never know how many people have been touched by their enthusiasm. I hope you never lose the teaching bug. Amelia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks

LikeLike

Simon, happy belated birthday.

I really enjoyed this post.

I especially liked your (full) report card – “his attitude towards his schoolwork must improve”. I guess you turned out alright in the end!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Stefanie

LikeLike

Hi Simon,

I enjoyed your birthday effort and especially your abservations about IC, my experience was much the same, as you probably can guess!

The pictures I sent at Xmas show what entomology I do these days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Stu

LikeLike

Pingback: Amateur, professional and academic interactions: A day with the British Entomological and Natural History Society | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Celebrating being 60 by walking the Yorkshire Coast – a pictorial record | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Compilation of stories on paths to ecology | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: Why, to my wife’s dismay, I made a late academic career move | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Professor Emeritus – the final instar? | Don't Forget the Roundabouts