I think, that most, if not all entomologists, will confess to a bit of funding envy when talking with those of their colleagues who work with the “undeserving 3%”, the large charismatic mega-fauna and the modern dinosaurs. The terminology gives us away, although the evidence is overwhelmingly on our side (Leather, 2009). As entomologists, particularly those of us working in the field, we are used to reporting numbers collected in the tens of thousands (Ramsden et al., 2014 ), if not the hundreds of thousands (Missa et al., 2009) and even a short six-week study can result in the capture of thousands of ground beetles (Fuller, et al., 2008). Naming our subjects, much as we love them, is not an option, even if we wanted to. Even behavioural entomologists counting individual flower visits by pollinators are used to dealing with hundreds of individuals. In the laboratory, although numbers may be smaller, say tens, we still assign them alphanumeric codes rather than names, even though one might look forward to counting the number of eggs laid by the unusually fecund moth #17 or hope that aphid #23 will be dead this morning as she is becoming a pesky outlier for your mortality data 🙂

Our colleagues who work with mammals in the field, seem however to adopt a different strategy. It appears quite common for them to name their animals as the following examples from Twitter make clear.

From her dissertation field note book, Erin Kane @Diana_monkey but not yet published.

Published data in McGraw et al., (2016) are from another study where the animals are not named.

Anthropomorphic judgement values

Anne being very involved with her cheetahs, although the paper (Hillborn et al., 2012) does not mention them by name.

Another example of subjects with names Hubel et al., 2016), but this time named in the paper.

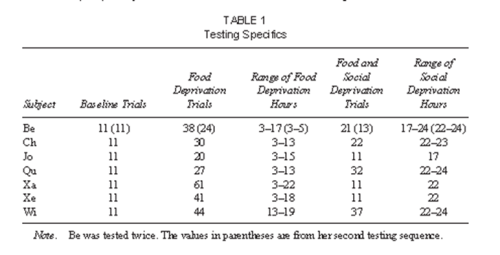

Although in the description of methodology and results animals are referred to as subjects, the Table gives it away! (Allritz et al., 2016).

Another example of named subjects (Stoinski et al., 2003).

More named subjects (Dettmer & Fragaszy, 2000), but as these were captive the names almost certainly not chosen by the observers.

In this case (Blake et al., 2016), use no human-based names either in the methods or tables, so exemplary, although of course I have not seen their field note books 🙂

My concern, highlighted by these examples, is that by naming their study animals, the observers are anthropomorphising them and that this may lead them to inadvertently bias their observations. After all, the names have not been chosen at random, and thus could influence the behaviours noted (or ignored). I say ignored, because of two very specific examples, there are more, but I have these two to hand.

Victorians used birds as examples of good moral behaviour, erroneously believing them to be monogamous, probably because of seeing the way they fed their chicks cooperatively. Tim Birkhead (2000)* quotes the Reverend Frederick Morris who in 1853 preached “Be thou like the dunnock – the male and female impeccably faithful to each other,” and goes on to point out that despite a hundred years of ornithological science it was not until the late 1960s that the promiscuous behaviour of female birds was revealed, interestingly enough coinciding with the new moral code of the 1960s.

Descriptions of penguin homosexual behaviour and their penchant for acts of necrophilia so shocked George Levick’s publishers that they removed them from his 1915 report but printed them and privately distributed them to selected parties marked as “Not for Publication” (Russell et al., 2012). He also transcribed his descriptions of this ‘aberrant’ behaviour in Greek in his notebooks, presumably to make it less accessible.

And finally from me, this recent report about ‘sacred and ritualistic’ behaviour in chimpanzees Kuhl et al (2016), where, I feel the authors have really allowed themselves to over-anthropomorphise with their subjects, very much to the detriment of scientific detachment. I have yet to find an entomologist who agrees with their interpretation. http://www.nature.com/articles/srep22219

AND NOW SOMETHING NEW for my blog, an embedded comment/riposte. I thought that it would be useful to get a response from someone who works on large charismatic mega-fauna and who names their subjects. Anne Hilborn, whom many of you will know from Twitter as @AnneWHilborn, has kindly agreed to reply to my comments. In the spirit of revealing any possible conflicts of interest I should say that I taught Anne when she was an Ecology MSc student at Silwood Park 🙂

Over to you Anne…..

“Hello, my name is Anne and I name my study animals.”

Decades ago this might have gotten me jeered out of science, the assumption being that by naming my study animals I was anthropomorphizing them and that any conclusions I drew about their behavior would be suspect. Thankfully we (at least those of us who have the privilege of working on megafauna) have moved on a bit in our thinking and our ways of doing science.

There are two parts to Simon’s concern about naming study animals. One is that naming leads to anthropomorphization, the second is that the anthropomorphizing leads to biased science. I would argue that the naming of study animals doesn’t necessarily increase anthropomorphism. On the Serengeti Cheetah Project we don’t name cheetahs until they are independent from their mother (due to a high mortality rate). During my PhD fieldwork I spent a lot of time following a young male known as HON752MC (son of Strudel). Several months after I started my work he was named Boke. My interest in his behavior, my chagrin at his failures and happiness when he had a full belly didn’t change when he was named. Many of us get emotionally attached on some level to our study animals, whether they have names or numbers.

An interesting thing to ponder is that if naming does lead to anthropomorphizing, does it only happen when human names are used? What human characteristics am I likely to attach to cheetahs named Peanut, Muscat, Strudel, Fusili, or Chickpea?

As to whether anthropomorphism leads to biased science… it definitely can if, as Simon points out, certain behaviors are not recorded because they do not fit the image of the animal the researcher had in their head. I don’t have any data on this, but I suspect this is extremely rare now days. Almost all researchers have had extensive formal training and know the importance of standardized data collection. I study cheetah hunting behavior, and I record how long a cheetahs spends spend stalking, chasing, killing, and eating their prey. I record the number of animals in the herd they targeted, how many second the cheetah spends eating vs being vigilant, and at what time they leave the carcass. No matter my personal feelings or attachments to an individual cheetah, the same data gets recorded.

Research methods have advanced a lot in the past decades and we use standardized methodologies and statistics expressly to prevent bias in our results. Anthropomorphism is just one possible source of bias, others include wanting to prove a treasured hypothesis, the tendency to place plots in areas where you suspect you will get the best results, etc..

As Adriana Lowe (@adriana_lowe ) puts it “Basically, if you’ve got a good study design and do appropriate stats, you can romanticise the furry little buggers until the cows come home and it won’t have a massive effect on your work. Any over interpretation of results would get called out by reviewers when you try to publish anyway.”

Simon points out examples of people being shocked when birds didn’t follow the dictates of contemporary human morality. I would like to think that biologists no longer place human values on animals. I can admire hyenas because the females are bigger bodied and socially dominant to males, but that doesn’t mean I draw parallels or lessons from them to human society (not in the least because the females give birth through their elongated clitoris and the cubs practice siblicide). As scientists we are capable of compartmentalizing, of caring deeply for our subjects, of shedding a tear when Asti turns up with one cub when previously she had five, without that changing the way we record data. In our training as biologists, we are taught not impose our own feelings or values on our study animals. We may find infanticide in lions (Packer and Pusey 1983), extra pair copulations in birds and primates (Sheldon 1994, Reichard 1995), or siblicide in boobies (Anderson 1990) to be repugnant, but we record, analyze, and try to publish on the phenomenon all the same.

To go on the offensive, there are ways naming study animals actually improves data collection.

Again, Adriana Lowe “If you’re doing scan sampling for instance, so writing down all individuals in a certain area every 10 minutes or so, names help. At least for me, it’s harder to remember if someone is M1 or M2 than Janet or Bob, particularly if you have a big study troop/community. So it can improve the quality of the data collected if you’re less likely to make identification errors.”

Because of our own training and peer review, assigning emotions or speculating about the intent on animals rarely makes it into scientific papers. However the situation is very different for those of us who wish to present our results outside of the ivory tower. While fellow scientists might be willing to wade through dry descriptions about how M43 contact called 3 times in 4 minutes when he was no longer in visual contact with M44, the public is not. Effective science communication needs a story and an emotional hook to draw people in. It is much easier to do that when you tell a story about Bradley and Cooper and not M43 and M44. I will admit this does get into grey areas with the type of language we use outside of scientific papers. I tell stories about the cheetahs in my blog posts and even assign emotions to individuals. But if I am answering questions from the media or the public, I am still very careful not to make any definitive claims about behavior that haven’t been backed up by statistical analysis.

Here I use language and make assumption in tweets that I never would in a scientific paper.

There are a lot of issues that negatively affect the objectivity of science ie. the majority of funding going to well established entrenched researchers, papers being reviewed primarily by people from the same school of thought, the increasing pressure to have flashy results that generate headlines, but naming of study animals is not high on the list.

——————————————————————————————————————–

So now, over to you the readers, what do you think? Please comment and share your views or at the very least, please cast your vote.

VOTE NOW

References

Allritz, M., Call, J. & Borkenau, P. (2016) How chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) perform in a modified emotional Stroop task. Animal Cognition, 19, 435-449.

Anderson, D. J. (1990) Evolution of obligate siblicide in Boobies. 1. A test of the insurance-egg hypothesis. American Naturalist, 135, 334–350.

Birkhead, T. (2000) Promiscuity: An Evolutionary History of Sperm Competition and Sexual Conflict. Faber, London.

Blake, J.G., Mosquera, D., Loiselle, B.A., Swing, K., Guerra, J. & Romo, D. (2016) Spatial and temporal activity patterns of ocelots Leopardus pardalis in lowland forest of eastern Ecuador. Journal of Mammalogy, 97, 455-463.

Dettmer, E., and Fragaszy, D. 2000. Determining the value of social companionship to captive tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 3, 293-304

Fuller, R. J., Oliver, T. H. & Leather, S. R. (2008). Forest management effects on carabid beetle communities in coniferous and broadleaved forests: implications for conservation. Insect Conservation & Diversity 1, 242-252.

Hillborn, A., Pettorelli, N., Orme, C.D.L. & Durant, S.M. (2012) Stalk and chase: how hunt stages affect hunting success in Serengeti cheetah. Animal Behaviour, 84, 701-706

Hubel, T.Y., Myatt, J.P., Jordan, N.R., Dewhirst, O.P., McNutt, J.W. & Wilson, A.M. (2016) Energy cost and return for hunting in African wild dogs and cheetahs. Nature Communications, 7, 11034 DOI:doi:10.1038/ncomms11034

Kühl, H.S., Kalan, A.K., Arandjelovic, M., Aubert, F., D’Auvergne, L., Goedmakers, A., Jones, S., Kehoe, L., Regnaut, S., Tickle, A., Ton, E., van Schijndel, J., Abwe, E.E., Angedakin, S., Agbor, A., Ayimisin, E.A., Bailey, E., Bessone, M., Bonnet, M., Brazolla, G., Buh, V.E., Chancellor, R., Cipoletta, C., Cohen, H., Corogenes, K., Coupland, C., Curran, B., Deschner, T., Dierks, K., Dieguez, P., Dilambaka, E., Diotoh, O., Dowd, D., Dunn, A., Eshuis, H., Fernandez, R., Ginath, Y., Hart, J., Hedwig, D., Ter Heegde, M., Hicks, T.C., Imong, I., Jeffery, K.J., Junker, J., Kadam, P., Kambi, M., Kienast, I., Kujirakwinja, D., Langergraber, K., Lapeyre, V., Lapuente, J., Lee, K., Leinert, V., Meier, A., Maretti, G., Marrocoli, S., Mbi, T.J., Mihindou, V., Moebius, Y., Morgan, D., Morgan, B., Mulindahabi, F., Murai, M., Niyigabae, P., Normand, E., Ntare, N., Ormsby, L.J., Piel, A., Pruetz, J., Rundus, A., Sanz, C., Sommer, V., Stewart, F., Tagg, N., Vanleeuwe, H., Vergnes, V., Willie, J., Wittig, R.M., Zuberbuehler, K., & Boesch, C. Chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing. Scientific Reports, 6, 22219.

Leather, S. R. (2009). Taxonomic chauvinism threatens the future of entomology. Biologist, 56, 10-13.

McGraw, W.S., van Casteren, A., Kane, E., Geissler, E., Burrows, B. & Dsaegling, D.J. (2016) Feeding and oral processing behaviors of two colobine monkeys in Tai Forest, Ivory Coast. Journal of Human Evolution, in press.

Missa, O., Basset, Y., Alonso, A., Miller, S.E., Curletti, G., M., D.M., Eardley, C., Mansell, M.W., & Wagner, T. (2009) Monitoring arthropods in a tropical landscape: relative effects of sampling methods and habitat types on trap catches. Journal of Insect Conservation, 13, 103-118.

Packer, C. & Pusey, A.E. (1983) Adaptations of female lions to infanticide by incoming males. American Naturalist, 121, 716–728.

Ramsden, M.W., Menéndez, R., Leather, S.R., & Wakkers, F. (2014) Optimizing field margins for biocontrol services: the relative roles of aphid abundance, annual floral resource, and overwinter habitat in enhancing aphid natural enemies. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment, 199, 94-104.

Reichard, U. (1995) Extra-pair copulations in a monogamous gibbon (Hylobates lar). Ethology ,100, 99–112.

Russell, D.G.D., Sladen, W.J.L. & Ainley, D.G. (2012) Dr. George Murray Levick (1876-1956): unpublished notes on the sexual habits of the Adélie penguin. Polar Record, 48, 387-393

Sheldon, B. C. (1994) Male phenotype, fertility, and the pursuit of extra pair copulations by female birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 257, 25–30.

Stoinski, T.S., Hoff, M.P. & Maple, T.L. (2003) Proximity patterns of female western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) during the six months after parturition. American Journal of Primatology, 61, 61-72.

Post script

I said that entomologists don’t name their study animals but they do name their pets. Some of our PhD students had an African flower

Soulcleaver; despite his name he seems quite cute when viewed side-on, perhaps even with a cheeky grin, although as an entomologist I couldn’t possibly say that 🙂

beetle, Mecynorhina ugandiensis, which they named Soulcleaver, and I know that some beekeepers name their Queens https://missapismellifera.com/2016/03/17/the-decay-of-spring/

*note that Tim Birkhead also falls into the very trap that he describes by using the word promiscuous in the title of his book, a human judgemental term relating to moral behaviour, multiple mating would have been more appropriate.

Excellent post! As an insect ecologist/entomologist, no I have never named my study animals. But I still pick my favourites, as taxonomic groups during observation or individuals while I’m identifying them! Agree with Anne, naming animals is really a great science communication tool more than a bias for data collection. Although I’m not sure it would work for insects….there’s an interesting study in that! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there are important pitfalls to be aware of, but it is very reductionist, Skinnerian and barren to think of animals as unemotional physical particles.

We are social mammals, and can empathize and understand swathes of behaviour because of that. Misunderstand too, yes, but we can discuss, correct, and even learn from biases found in our built in ‘apparatus’.

The reality is that we overlap with animals – not the other way around. I have a problem with the term anthropomorphism as a concept. We are recognising elements of our own make up, and where these came from in nature – not projecting unusual & unnatural qualities outwards onto a separate and alien domain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just wanted to clarify that the picture of my field notes is not related to the paper you cited. My field notes are from dissertation data collection on Diana monkeys, and though I haven’t published data from them yet, there are a number of other publications the same groups. Where individuals are identified in publications, they tend to use codes rather than names (though not always; I have a paper in press which identifies individuals by name because it is a brief communication describing a discrete event, and using codes made it *way* too complicated.

Anyway, the paper you cited is on oral processing behavior in two different species of monkey living in the same forest where I conduct my dissertation research. We don’t have named individuals in those groups, and data in that paper are reported by age and sex class, not by individual.

An interesting question, nonetheless!

LikeLike

Thanks, I will edit accordingly

LikeLike

We don’t really run into this problem as entomologists, because we do not usually observe differences between individual insects which we would ascribe to ‘personality’. Do we?!

Working with fellow mammals, be it meerkats or chimpanzees, different personalities must be all too apparent, as with our pet dogs and cats. Whether you call each animal Jane or J11, Bill or B12, there is no getting away from the fact that we will relate to these animals as individuals. It must be important to build in checks to avoid observer biases in the research. But humans cannot remain automatons and avoid such identification, in my mind.

Jane Goodall is the best example of of this, and she was criticised at the time for moving away from using numbers for animals. Yet her close empathy with her subjects led to new discoveries about chimp behaviour and a better understanding of the fact that many human feelings and emotions are shared by animals. That said her work is not without its critics.

I think including names of animals in research papers is being honest by mammal researchers. It must be hard to spend years studying meerkats and not secretly give them names! Yet I still think it is possible to be objective, or as objective as we can be observing creatures with such obviously similar feelings and emotions as ourselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In a classic entomology paper, Bernd Heinrich and Scott Collins named their chickadees “Caterpillar leaf damage and the game of hide and seek with birds”. In fact, they even nicknamed one of their birds… Fernald was referred to as “Fern” for the entirety of the paper after the first mention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think this is a thesis that could be tested, with a bit of work. I can even think of a methodological journal that would be interested in publishing it.

FWIW the only species I’ve worked with scientifically is cereal powdery mildew. We didn’t use names.

LikeLiked by 1 person

might take you up on that 🙂

LikeLike

I name my mouse lemurs, because I consider it as a way to take into account their between-individual variation – so kind of as a way of acknowledging that they are individuals.

Not so long time ago – twenty years ago or so – biologists would have thought that the idea of assigning distinct personalities for animals is preposterous. But nowadays we know that there is, in pretty much any group of animals which have been studied. (In one field course, I was involved with a learning experiment with carabid beetles, and I’m sure as hell that there’s huge variation in their learning capabilities.)

I’m not directly doing behavioural studies with my mouse lemurs, but I’m doing parasitological work. That means that I do not have time nor interest to do the very complicated and time-consuming behavioural experimentattion. Nevertheless, my mouse lemurs have their personalities and I try to get to know them so I know who I’m working with, as their personalities are sure to matter for epidemiology of parasites. As I name them, I get to know them a bit better.

Now, as Anne described, I don’t really have data, but I have a lot of hunches. Hunches don’t get into papers, but hunches do have their effect on what questions I ask and what I think is possible and what is not. (I suspect any organismal biologist have their own set of hunches – unpublished, unproven silent knowledge which directs their methods and research questions). So, I have some kind of intuitive knowledge on what mouse lemurs would do and what they wouldn’t do – though none of it scientifically proven. As a consequence, I have a nice pile of ideas for Master’s student to do their thesis to really test out some of these intuitive things.

I see naming my study subjects as one source of this silent knowledge within the field. It may or it may not be correct knowledge and it remains to be proven true or falsified. But it does direct in any case how I do my research and analyze my results. It’s just that I can’t – as Anne descrived – write it in my papers without the actual “objective” data.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks – interesting points

LikeLiked by 1 person

We name our bee hives as their behaviour is different but it is very important to watch the behaviour of the colony. However, as Anne explains we would get very muddled discussing number 2 or number 3. Amelia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Roundabout Review of the Year – highlights from 2016 | Don't Forget the Roundabouts