From The Tribulations of Tommy Tiptop (1887)

I have written briefly about this before but having fairly recently (November 2017) been asked to give a talk at a conference in Cambridge called A Bug’s Life – Creeping and Crawling through Children’s Literature, I felt inspired to revisit the topic. This was a new adventure for me, first because almost everyone there was not a scientist, let alone an entomologist and second it was the first time I had been to a conference on a Saturday😊 I was given a half hour slot* to expound on The Good, the Bad and the Plain Just Wrong which I had decided to make my topic.

I should point out at the onset in case anyone is expecting a comprehensive survey of the genre, that this is a very idiosyncratic and personal account. Consider it a potted history of my encounters with insects in children’s books over the past 57 years or so. Insects have appeared in books for children for at least 200 years, more if you count Aesop’s Fables. Just to warn you, I’m going to jump directly from Aesop to the middle of the Nineteenth Century and then meander my way to the present day. Generally speaking, adult fiction, like adult films tends to cast arthropods as the villains, although there are some notable exceptions, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, being a fantastic positive example.

Insects as baddies in adult fiction.

In my talk, I used Aesop to segue from adult to children’s fiction, in his day, Aesop was using his fables to talk to adults; it is only in relatively modern times that his tales have been used to instil morals into children (Locke, 1693). It may come as a surprise to know that Aesop told, not wrote, although they are now written down, about 350 fables, of which only sixteen mention insects, less than 5%, so even then institutional verterbratism was alive and kicking 🙂

Aesop and his fables – somewhat depauperate in arthropod examples

Children’s literature continued to be highly moralistic in tone and this was certainly the case in the nineteenth century as the German classic Struwwelpeter where children who are less than good meet horrible ends, such as Frederick who enjoyed pulling the legs and wings off flies as well as other reprehensible acts.

Frederick gets his comeuppance in Struwwelpeter (Heinrich Hoffman, 1844)

If not moralistic, then books for children tended to be instructive. Two excellent and contrasting examples, firmly based in entomology, come from Ernest van Bruyssel (1870) and Charles Holder (1882). In Van Bruyssel’s (1827-1914) book, the main character falls asleep underneath a pear tree and dreams that he has shrunk to insect size and comes face to face with the invertebrates associated with the tree and their activities. He describes these in anthropomorphic terms as here in this description of mole crickets mating “As the spouses drew nearer, the silver bell rang less loudly and more airily. The motions of the wings of the male, violent of late, which produced this curious sound, grew feebler by degrees. He was hid under the grass, and my mole-cricket too disappeared there. I heard two or three more indistinct and plaintive notes, and then the meadow was ‘quite quiet”.

Ernest van Bruyssel 1827-1914 – with fantastic and very clever illustrations

A reminder to his young audience that our actions may have more consequences than we think

“Really I did deserve a chastisement for my intrusion into the meadow, the disastrous consequences of which I now had power to perceive to the full extent. I had bruised the tender stalks of springing grass, broken quantities of buds, and destroyed myriads of living creatures. In my stupid simplicity I had never had any suspicion of the pain I caused while perpetrating these evil deeds, and had been in a state of delight at the profound peace pervading the country, and the charms of solitude.”

Holder on the other hand, adopts a much more factual approach, albeit in somewhat fanciful language as in this description of the pupation process of a butterfly “Yes, the future imago is forming now; days of monotonous toil, of diligent accretion, of patient preparation, and of tedious torpor in the antechamber of mortality, shall result in that lovely winged thing, that shall float on the zephyr, and glitter in the noonday light”

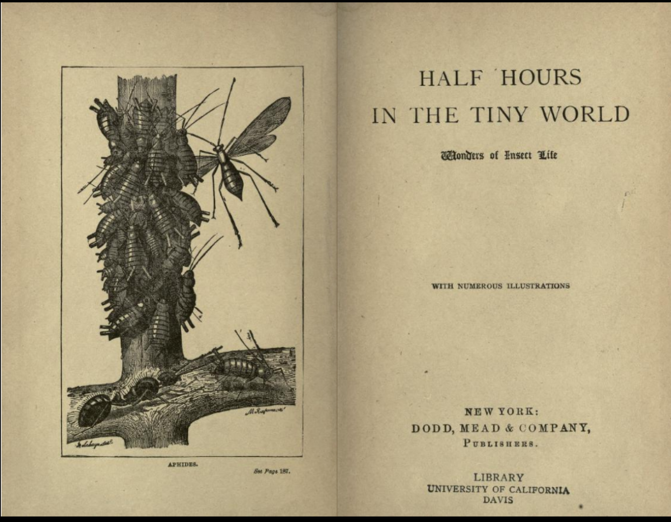

Any book with an aphid frontispiece gets my approval – Half Hours in the Tiny World by Charles Frederick Holder (1882).

Both authors convey the wonder of entomology to their audience in a memorable way but I suspect that van Bruyssel had a greater impact although the biology is, of course, more accurate and detailed in Holder.

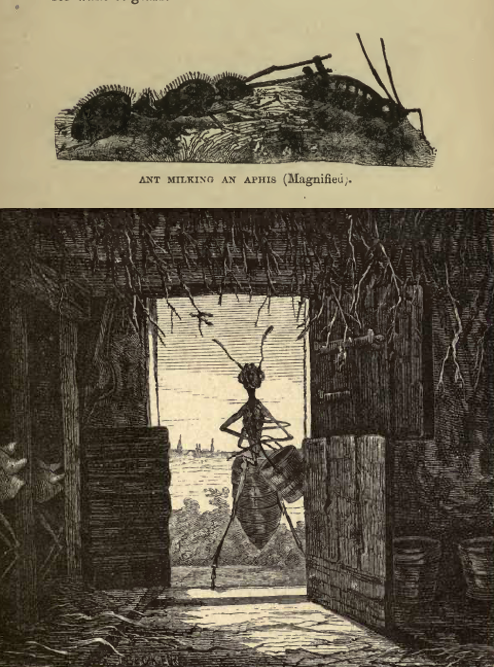

Two versions of ants getting honeydew from aphids, Holder at the top and van Bruyssel at the bottom. Note the clever way in which the siphunculi of the aphids are made to give the appearance of cow horns in the van Bruyssel illustration.

One of the other things I really like about van Bruyssel’s book is that despite being very anthropomorphized, it is possible to identify the insects with some certainty.

Instantly recognisable to an entomologist

1883 saw the publication of an enduring classic, The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi, yet again a book with a moral message, but with an insect playing a leading role, The Cricket, not Jiminy Cricket as in the Disney version, just The Cricket. Until Disney got hold of it the cricket tended to look like a cricket. My favourite version is the 1959 edition illustrated by the great Libico Maraja, which I am lucky enough to own, both the one I had as a child and also the French edition which I found in the attic of our French house in 2016.

Realistic and not so realistic versions of The Cricket

Similar to Struwwelpeter but written some forty years later, is The Tribulations of Tommy Tiptop (1887), the story of a boy who delights in torturing animals, especially insects and is punished by a series of nightmares in which his victims get their revenge.

Tommy Tiptop meeting an appropriately grisly end at the tarsi of easily identifiable insects (1887)

Jumping forward to the early 20th Century we have Gene Stratton Porter’s A Girl of the Limberlost, the story of a girl who to earn money to continue her education, catches butterflies to sell to collectors and museums. The notable aspect of this book is that the negative effects of deforestation and agricultural intensification on the abundance of butterflies is highlighted; something that is much in the news now. A shame people didn’t take more notice of this a hundred years ago.

A book with an ecological message and lots of insects

Moving on and becoming poetical, Alexander Beetle in A A Milne’s poem Forgiven is a great commentary, at least to me, that most children start off by loving insects and that it is adults who turn them against them. Something I have noticed on many outreach occasions.

Alexander Beetle, definitely a Carabid, and probably Pterostichus sp. (Milne, 1927)

An example of a missed opportunity by a great nature writer, is Brendon Chase (1944) in which three brothers run away from home and spend several months living wild in the woods. The only insect that gets a mention is a dragonfly and then only very briefly. What a missed opportunity 😦

A missed opportunity – birds, mammals and fish do very well, insects might as well not exist

Generally speaking, books for children that feature insects do tend to cast them in a favourable light, what is at fault tends to be the representation of insect anatomy and biology, although this is more often than not, down to the illustrator, not the author.

Next up chronologically, are the very cute Ant & Bee books by Angela Banner. I didn’t actually own any of these as a child, they belonged to my younger siblings, but I did enjoy reading them J The gross anatomy is not too bad, although bee is male and eats cake at times, nevertheless they present a very favourable view of two insects that adults perceive as nuisances and likely to bite and/or sting. Needless to say, my children all had copies bought for them when they were learning to read and write.

Angel Banner’s delightful Ant & Bee books (1950-1972)

The next book, although written before the Ant & Bee books didn’t come my way until the mid-1960s when I discovered the Jungle Doctor series in the YMCA Library in Hong-Kong. The author of the series, Paul White, was a medical missionary in Africa from 1939-1941; as a result, the insects he mentions, tend to be of medical importance although as in my example here, the problem was more general, but just as dangerous, a home invasion by Driver Ants.

From Jungle Doctor and The Whirlwind (1952)

.

Although not strictly about insects, and in my opinion not really a children’s book, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was a staple of the UK secondary school English curriculum for many years and the cover illustrations of a large proportion of the various editions since it was published in 1954, feature flies, more often or not fanciful rather than actual.

A very non Dipteran fly!

Inaccurate representations of insects are easy to find as anyone who has read Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach (1961) will know. I sometimes feel that the more illustrious the illustrator the less realistic the insect subjects.

Three different takes on the inhabitants of the giant peach

Entomologists often wonder if Eric Carle had ever seen a lepidopteran caterpillar, but to be fair the story gives a positive view of insects, albeit it being fairly difficult to portray butterflies negatively.

Very unlike a lepidopteran larvae, Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969)

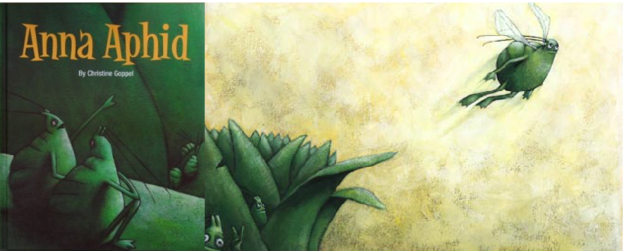

I may be a bit of entomological anatomy pedant, but I am prepared to forgive Christine Goppel her extremely inaccurate portrayal of aphid taxonomy and biology. Any book that shines a positive light on aphids gets my vote 🙂

Anna Aphid, by Christine Goppel (2005). So wrong in so many ways, but so right in a weird sort of way 🙂

Equally guilty of gross insect anatomical misrepresentation are Julia Donaldson and Lydia Monks, but again they put a positive spin on their insect star, but then they have a head start because ladybirds already enjoy good press.

What can I say? Grossly inaccurate but a positive spin.

More worthy of praise are the delightful books by Antoon Krings, who manages to imbue insects that most adults and some children view with fear and loathing, fleas and wasps for example, with cuteness joy.

Two of Antoon Kring’s anatomically incorrect, but lovable insects from his series Drôles de petites Bêtes (Funny little beasts).

There is, in my opinion as I have written before, no excuse to simplify illustrations to mere caricatures. Compare the two examples, below, both written for children of the same age; in the 1906 book you can recognise not only the insect species but you can also identify the plants, including the grasses, the 2009 book is a very much dumbed down affair.

Two contrasting levels of realism, top frame; Sibylle von Ohlers’ Etwas von de Wurzelkindern (1906), bottom frame Birgitta Nicolas’ Der kleine Marienkäfer und seine Freunde (2009).

And finally, for the older reader, I recently discovered Bug Muldoon, the eponymous hero of Paul Shipton’s insect detective series. Leaving aside the anthropomorphism of the invertebrate characters, the biology is quite accurate, unlike the cover illustrations which are considerably less so, but the story lines inside are very entertaining.

A great story let down by the illustrator (1995). Those are definitely not compound eyes!

And finally, I will reiterate yet again, my praise for Maya Leonard and her Beetle Boy series, in which the reader is carried along on a tumultuous, emotional roller-coaster of adventure and exposed to a lot of real entomology. The best insect-based fiction to date and will, I think, not be surpassed for some time.

A joy to read and very soundly based entomologically

Reference

Locke, J. (1693) Some Thoughts Concerning Education

*

I also even more recently gave a very condensed version of this talk at The Royal Entomological Society’s annual meeting, ENTO18 last month.