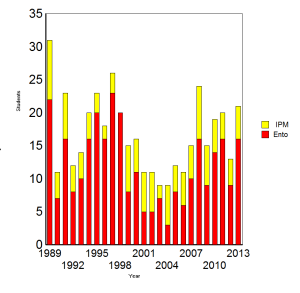

Over the course of the last decade I have come to the conclusion that British undergraduates have no idea of what pest management actually is. For the last thirty years or so, I have run a suite of MSc courses, initially at the Silwood Park campus of Imperial College and since 2012, at Harper Adams University, the leading land-based university in the UK. The four MSc courses I run are Conservation and Forest Protection, Ecological Applications, Entomology and Integrated Pest and Disease Management. These are, as you can see, pretty much specialist vocational courses. The students who do these courses are highly motivated and come from a range of backgrounds. Many had established careers in other areas and found those careers lacking. Others have had a burning desire to embark on advanced training in entomology since they were at school and been deeply frustrated that no undergraduate degrees exist in the UK in that subject. [The last BSc in Entomology in the UK was awarded in 1993 by Imperial College to Andy Salisbury (now Dr Andrew Salisbury and Senior Entomologist at the Royal Horticulture Society’s research offices at Wisley]. Yet others have developed an interest in one of the areas covered by my MSc courses as undergraduates and decided to make a career in those areas, but found that their BSc degrees had not prepared them to the required level in their chosen subject and that they needed the extra training provided by a postgraduate course. The interesting thing to me is how the absolute interest in integrated pest management has remained at pretty much the same level year on year, at just under 5 with a high of 9 students in 1989 and in 1998 no students at all. Over the same period the average number of entomologists on the course was twelve. As a proportion of the student body the pest management contingent has ranged from a very disappointing zero to the memorable year, 2004, when there were twice as many pest managers as entomologists, albeit out of total student body of only nine.

Pest managers are in great demand from industry –biological control and agrochemical companies have more positions than there are suitably qualified graduates; yet undergraduates seem reluctant to train in this area. I think that there are two root causes for this problem; a lack of exposure to the subject as undergraduates and a misunderstanding of exactly what pest managers are and what they actually do. Mention pest management to most people, not just students, and their first reaction is rats, cockroaches and Rentokil* operatives spraying.

Yes pest control does involve poisoning vermin and spray operations against domestic insect pests, but that is only one very minor, albeit important, aspect of pest management. Pest management, or as it is more formally known, Integrated Pest Management, is the intelligent selection and use of pest control measures to ensure favourable economic, ecological and sociological consequences. Yes this does include the use of pesticides but only as part of an integrated programme that could include biological control, the use of resistant plant varieties, and the diversification of the farm landscape through conservation headlands, and cultural methods such as crop rotation or inter-cropping. Even scare-crows, traditional or modern, can be part of an IPM programme. The list goes on and all this is backed up by a detailed knowledge and understanding of the biology and ecology of the pest species, their natural enemies and the habitats that they live in.

The idea of pest management is not an entirely modern one ; Benjamin Walsh a British born pioneer applied entomologist working in the USA, said in 1866, and I quote, “Let a man profess to have discovered some new patent powder pimperlimplimp, a single pinch of which being thrown into each corner of a field will kill every bug throughout its whole extent, and people will listen to him with attention and respect. But tell them of any simple common-sense plan, based upon correct scientific principles, to check and keep within reasonable bounds the insect foes of the farmer, and they will laugh you to scorn”. I consider this to be the first modern reference to integrated pest management.

Pest managers do not just work in domestic and urban situations. Most pest managers, as opposed to pest control operatives work in agriculture, forestry and horticulture, safeguarding our crops and ensuring global food security. Pest managers, because of the complexity of the problems facing sustainable crop production in the modern world, have to have a much greater depth and breadth of knowledge than pure ecologists. Although many pest managers have entomological backgrounds, they also have a more than nodding acquaintance with plant pathology, nematology and pesticide application and chemistry. They also need to have a good grasp of the economics of both pest control and the farming/cropping system that they are working in. They must fully appreciate what is feasible and appropriate in the context of the farmer’s/forester’s year, budgets and targets in terms of yields and profits. There is no point in coming up with the ideal ecological or conservation solution that cannot be implemented because of the constraints of the real world. Pest managers, even those working in academia, interact closely with their end-users, to ensure a reduction in pest numbers and abundance, not necessarily eradication, which is acceptable to growers, society and the natural world. As Lorna Cole said on Twitter on September 8th 2013….

So when you hear the word pest management in future, don’t just think spray, think conservation headlands, beetle banks, biological control, crop rotation, resistant varieties, chemical ecology, forecasting, monitoring , cultural control, holistic farming, multi-purpose forestry, sociology, economics and sustainability. These are the elements of the armoury most commonly used by pest managers, not pesticides as so many people mistakenly think.

So for prospective students, don’t be put off by the word pest, if you want an exciting, satisfying and possibly international career, embrace the application of ecology and make a difference to the world. Become a pest manager. Without integrated pest managers food production will never be sustainable or as ecologically friendly as it now is.

Post Script

Sadly, even to this day (it was much worse when I started my career), there is a perception among some academics that being applied is second best; on one memorable occasion I was introduced to some visitors by one of my colleagues as, “this is Simon Leather, he’s an ecologist, ALBEIT, an applied one”

Post post script

For those interested in joining the MSc course in Integrated Pest Management based at Harper Adams University here is the appropriate link. I should also add that unfortunately we are NOT able to offer three annual Scholarships funded by the Horticultural Development Council, HDC, of £5000 each to particularly deserving students as despite ALL our graduates finding employment in the industry they felt that the scheme was not working!

*and even that is something of a stereotype – yes Rentokil and similar organisations spend a lot of time spraying for domestic pests but many of their staff are entomologically trained and environmentally aware, and I should know as I have taught some of them 🙂