I know we deal with invertebrates but the exoskeleton of entomology doesn’t quite hack it 😊 There is a tendency within academia, perhaps not as marked as it was when I entered it, to be somewhat dismissive, even scornful, when it comes to natural historians and amateurs. I once had a bit of an in-print argument with the late Denis Owen about the validity of data collected by ‘amateurs’ (Leather, 1990), which I found a bit surprising considering his wife Jennifer’s deep and life-long involvement with that type of data (Owen, 2010).

I have been a ‘professional’ entomologist for more than forty years and although I may, in the past, when I was imbued with the arrogance of youth, have made remarks about stamp collecting and lack of scientific method, I have always been in awe of the taxonomic expert, whom at a glance can accurately (most of the time) identify an insect to species. Me, I’m pleased when I get the family right. I remember when I was an undergraduate sitting round a light trap on our field course, being stunned by Judy Honecker (where are you now?) shouting out the names of the moths as they flew into it – all done by the mysterious jizz. She may of course, have been taking advantage of our ignorance, but I don’t think so.

I don’t think, even now, that many academic, research-active, professional entomologists, or ecologists really appreciate the service that the amateur entomologist or in a broader sense, natural historian, provides to the professional community. I am a long-time member of the British Entomological and Natural History Society (BENHS) which means that a copy of the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History pops through my letter box every three months. Every time I open a copy of this little journal I am humbled by

Latest issue of the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History

the erudition displayed by the contents. You won’t find professionally crafted accounts of large-scale field studies/experiment or complex laboratory experiments, analysed using the most complicated analysis that packages such as R or SPSS can spit out by any means. What you will find, and this is perhaps where the slightly scornful attitude to the ‘amateur’ has its roots, are reports of insects found while on holiday in Spain or closer to home* and accounts of the annual exhibition. You will also find note of the first records of species in the UK, new host records, be they plants or other animals, and yes, also reports of experimental work. The style may not be as ‘scientific’ as that found in mainstream scientific journals, but that does not detract from their value. The thing that really blows my mind about the BJENHS and others of its ilk such as the Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine, (in both of which I have published), are the numbers of new records reported and the identification skills that these demonstrate of the authors. It struck me that whereas those entomologists with similar skills that work within academia, either in museums or universities, are described as systematists (naturalists engaged in classification) or taxonomists (biologists that groups organisms into categories) these expert amateurs didn’t seem to have a single word to describe them. I of course resorted to Twitter to see if anyone out there knew better.

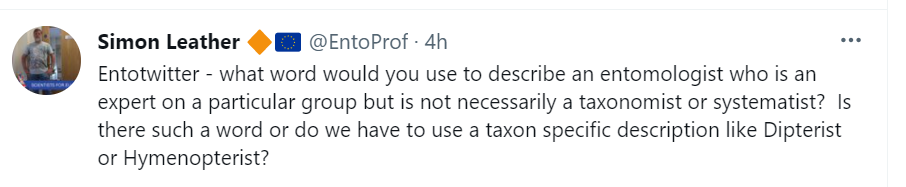

I received a number of responses, the one below summing up the most common answers.

Pretty much the status quo.

One person suggested parataxonomist, which I feel means an entirely different thing, being someone who has been trained to have “expertise is in collecting specimens, mounting them, and performing preliminary sorting of the specimens to morphospecies” (Basset et al., 2000).

What I do think we can all agree on, is that the county recorders, the various group specialists and more general natural historians, are what I would term professional amateurs. They are not paid for what they do, most have jobs outside entomology, or are, in many cases, retired, but they approach their subject in a thoroughly professional way, keeping impeccable records and disseminating their findings through publications, talks at meetings and running (or helping run) training courses. They do a huge service for entomology, not just by providing data for the ‘professionals’ to mine and analyse, but also by encouraging others to enter the field. The professional and the professional amateur can, sometimes exist in the same person, I was for example, once President of the Amateur Entomologist’s Society and the current President, Erica McAlister (@flygirlNHM, for those of you on Twitter), is also a professional entomologist.

Richard Jones rather neatly summing it all up.

There is now, however, a whole new category of amateur. Citizen science has unleashed the ‘amateur amateur’ into the wild, albeit many stray no further than their gardens. Citizen science, once a bit marginalised, is now pretty much mainstream is fully recognised by the professional ecologists and entomologists as a hugely important contribution to their disciplines Bates et al., 2013; Pernat et al., 2021). The two most publicised UK examples are the Big Butterfly Count (incidentally this year’s launch coinciding with the publication of this post) and the Big Garden Birdwatch, both of which my wife and I do. Despite having my name on ten papers dealing with birds, I count myself when it comes to the latter, as being a true ‘amateur amateur’ 😊

Citizen science projects span disciplines and the globe. You can take part in a ‘bioblitz’, record the timing of budburst, the number of plants in flower on a particular date, join in the UK ladybird survey, see how many birds you can count over the Christmas period, and many, many others.

I think it is extremely important to take note of the quote below. It explains to some extent, why in the past, and sadly, to a certain extent, why some (not many thankfully) professional scientists still tend to treat citizen science with less respect than it deserves.

“Traditionally, we think in terms of a data-gathering component of science, a data analysis component of science, and an interpretive “discussion” component of science. As well, the scientific method is typically thought of as being hypothesis driven (with the hypothesis or “question”preceding data collection), and in mainstream science the process of generating and testing hypotheses is the domain of the researchers – those people who are unequivocally “scientists”. In citizen science, the participants are almost exclusively involved in data gathering alone, but most projects include the promise that anyone is welcome to follow through with their own analyses and interpretations. This is the key element that makes citizen science “democratic”, even if a few participants follow up with analyses of their own. “Citizen Scientist” is, therefore, best understood as an honorary title, given to anyone who participates in any level of the scientific enterprise, on a voluntary basis, with the proviso that that most participants are involved only in data collection.” Acorn (2017)

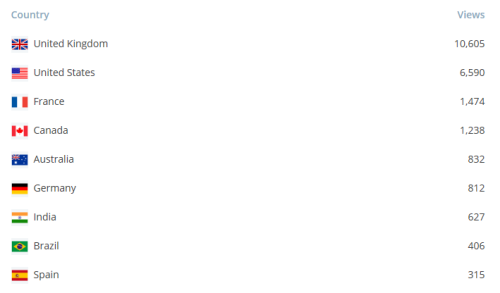

The data that we collect as citizen scientists is not wasted, and compares well with the data collected by the professionals (Pocock et al., 2015; Pernat et al., 2021) and as the picture below illustrates, is of immense value to entomologists and ecologists.

Roger Morris at Dipterist’s Forum June 27th 2021 ‘When I started it was as rare as rocking horse faeces’ – Roger Morris talking about recording Rhingia rostrata. Roger is highlighting why recording schemes are so useful. Picture from Twitter via @FlygirlNHM)

Just to reiterate the importance of these glorious amateurs. Just as those insect host records collected and published by the professional amateurs enabled the late Sir Richard Southwood to restart the species-area concept (Southwood, 1961) and give many of us an opportunity to lengthen our publication lists, so today’s army of professional and amateur amateurs are providing data for a new generation of entomologists and ecologists to help understand and explain the changes we are seeing in insect abundance and distribution (e.g. Werenkraut et al., 2020). It is very important that their contribution is neither overlooked nor unrecognised. Without them we would be lost.

Did you know that the oldest (unless you know of an older one?) Citizen Science project in the world is the Christmas Bird Count in the USA, which was started in 1900?

References

Acorn, J. (2017). Entomological citizen science in Canada. The Canadian Entomologist, 149, 774-785.

Basset, Y., Novotny, V., Miller, S.E. & Pyle, R. (2000) Quantifying biodiversity: experience with parataxonomists and digital photography in Papua New Guinea and Guyana. BioScience, 50, 899-908.

Bates, A.J., Sadler, J.P., Everett, G., Grundy, D., Lowe, N., Davis, G., Baker, D., Bridge, M., Clifton, J., Freestone, R., Gardner, D., Gibson, C.W.D., Hemming, R., Howarth, S., Orridge, S., Shaw, M., Tams, T., & Young, H. (2013) Assessing the value of the Garden Moth Scheme citizen science dataset: how does light trap type affect catch? Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 146, 386-397.

Leather, S.R. (1990) The analysis of species-area relationships, with particular reference to macrolepidoptera on Rosaceae: how important is insect data-set quality? The Entomologist, 109, 8-16.

Owen, J. (2010) Wildlife of a Garden; A Thirty-year Study, Royal Horticultural Society, London.

Pernat, N., Kampen, H., Jeschke, J.M. & Werner, D. (2021) Citizen science versus professional data collection: Comparison of approaches to mosquito monitoring in Germany. Journal of Applied Ecology, 58, 214-223.

Pocock, M.J.O., Roy, H.E., Preston, C.D., & Roy, D.B. (2015) The Biological Records Centre: a pioneer of citizen science. Biological Journal of the Linnaean Society, 115, 475-493.

Southwood, T.R.E. (1961) The number of species of insect associated with various trees. Journal of Animal Ecology, 30, 1-8.

Werenkraut, V., Baudino, F., & Roy, H.E. (2020) Citizen science reveals the distribution of the invasive harlequin ladybird (Harmonia axyridis Pallas) in Argentina. Biological Invasions, 22, 2915-2921.

*I remember reading with great amusement a short article in the Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine from the early part of the 20th Century describing the ‘discovery’ of a species new to Britain that had flown into the bathroom of the author (a retired Lt. Colonel if I recall correctly) while he was having a bath.