Unless you have been hibernating in a deep, dark cave or on another planet, you can hardly have missed the ‘insectageddon’ media frenzy that hit the UK (and elsewhere) on Monday (11th February).

This time the stimulus was a review paper outlining the dramatic decline in insect numbers, from two Australian authors (Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhus, 2019). Their paper, based on 73 published studies on insect decline showed that globally, 41% of insect species are in decline, which is more than twice that reported for vertebrates. They also highlighted that a third of all insect species in the countries studied are threatened with extinction. Almost identical figures were reported some five years ago (Dirzo et al., 2014), but somehow escaped the attention of the media.

I’m guessing that a clever press release by either the authors’ university or from the publisher of Biological Conservation set the ball rolling and the appearance of the story in The Guardian newspaper on Monday morning got the rest of the media in on the act.

The headline that lit the fuse – The Guardian February 11th 2019

The inside pages

A flurry of urgent phone calls and emails from newspapers, radio stations and TV companies resulted as the various news outlets tried to track down and convince entomologists to put their heads above the parapet and comment on the story and its implications for mankind. I was hunted down mid-morning by the BBC, and despite not being in London and recovering from a bad cold, was persuaded to appear live via a Skype call. A most disconcerting experience as although I was visible to the audience and interviewer, I was facing a blank screen, so no visual cues to respond to. According to those who saw it, it was not a disaster 🙂 Entomologists from all over the country, including at least three of my former students, were lured into TV and radio studios and put through their entomological paces.

Me, former student Tom Oliver (University of Reading), Blanca Huertas (NHM) and former student Andy Salisbury (RHS Wisley), getting our less than fifteen minutes of fame 🙂

Me, former student Tom Oliver (University of Reading), Blanca Huertas (NHM) and former student Andy Salisbury (RHS Wisley), getting our less than fifteen minutes of fame 🙂

As far as I know, we all survived relatively unscathed and the importance of insects (and entomologists) for world survival was firmly established; well for a few minutes anyway 🙂

It is the ephemeral nature of the media buzz that I want to discuss first. Looking at the day’s events you would be forgiven that the idea of an ecological Armageddon brought about by the demise of the world’s insects was something totally new. If only that were so.

Three years of insect decline in the media

The three years before the current outbreak of media hype have all seen similar stories provoking similar reactions, a brief flurry of media attention and expressions of concern from some members of the public and conservation bodies and then a deafening silence. Most worrying of all, there has been no apparent reaction from the funding bodies or the government, in marked contrast to the furore caused, by what was, on a global scale, a relatively minor event, Ash Die Back. Like now, I responded to each outcry by writing a blog post, so one in 2016, one in 2017 and another last year.

So, will things be different this time, will we see governments around the world, after all this is a global problem, setting up urgent expert task forces and siphoning research funding into entomology? Will we see universities advertising lots of entomologically focused PhD positions? I am not hopeful. Despite three years of insectageddon stories, the majority of ecology and conservation-based PhDs advertised by British universities this autumn, were concerned with vertebrates, many based in exotic locations, continuing the pattern noted many years ago. In terms of conservation and ecology it seems that funding is not needs driven but heavily influenced by glamorous fur and feathers coupled with exotic field sites (Clarke & May, 2002).

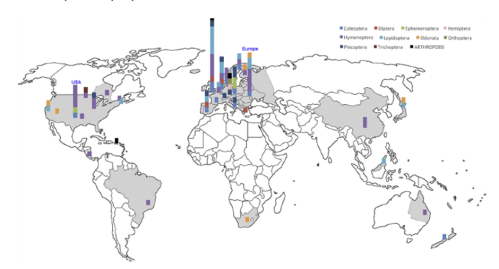

The paper that caused the current media outbreak (Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhus, 2019) although hailed by the media as new research, was actually a review of 73 papers published over the last several years. It is not perfect, for one thing the search terms used to find the papers used in the review included the term decline, which means that any papers that did not show evidence of a decline over the last forty years were not included e.g. Shortall et al. (2009; Ewald et al. (2015), both of which showed that in some insects and locations, populations were not declining, especially if the habitats that they favoured were increasing, e.g. forests, a point I raised in my 2018 post. Another point of criticism is that the geographic range of the studies was rather limited, almost entirely confined to the northern hemisphere (Figure 1). Some commentators have also criticised the analysis, pointing out that it was

Figure 1. Countries from which data were sourced (Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhus, 2019).

not, as stated by the authors, a true meta-analysis but an Analysis of Variance. Limitations there may be, but the take home message that should not be ignored, is that there are many insect species, especially those associated with fresh water, that are in steep decline. The 2017 paper showing a 75% reduction in the biomass of flying insects in Germany (Hallmann et al., 2017), also attracted some criticism, mainly because although the data covered forty years, not all the same sites were sampled every year. I reiterate, despite the shortcomings of both these papers, there are lots of studies that show large declines in insect abundance and they should not be taken lightly, or as some are doing on Twitter, dismissing them as hysterical outpourings with little basis in fact.

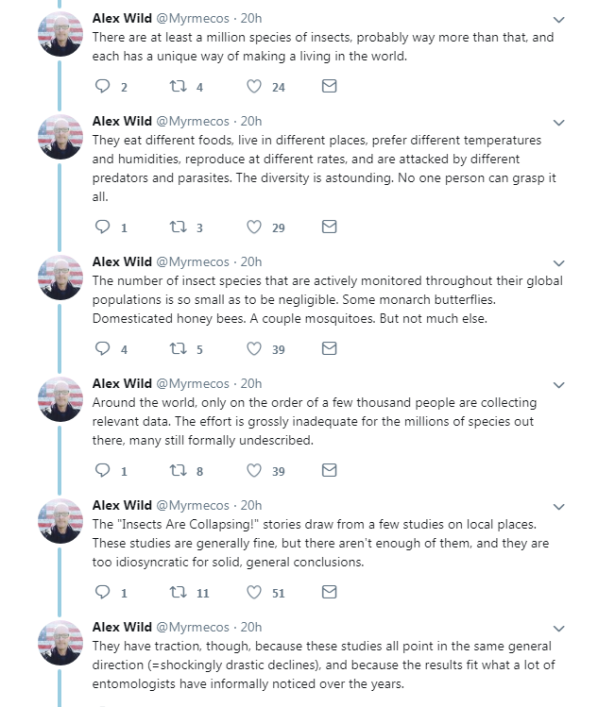

It is extremely difficult, especially with the lack of funding available to entomologists to get more robust data. The Twitter thread below from Alex Wild, explains the problems facing entomologists much more clearly and lucidly than I could. Please read it carefully.

Masterly thread by Alex Wild – millions of insects, millions of ways to make a living and far too few entomologists

I am confident that I speak for most entomologists, when I say how frustrated we feel about the way ecological funding is directed. Entomologists do get funding, but a lot of it is directed at crop protection. Don’t get me wrong, this is a good thing, and something I have benefited from throughout my career. Modern crop protection aims to reduce pesticide use by ecological means, but we desperately need to train more entomologist of all hues and to persuade governments and grant bodies to fund entomological research across the board, not just bees, butterflies and dragonflies, but also the small, the overlooked and the non-charismatic ones (Leather & Quicke, 2010). A positive response by governments across the world is urgently needed. Unfortunately what causes a government to take action is hard to understand as shown by how swiftly the UK government responded to the globally trivial impact of Ash Die Back but continues to ignore the call for a greater understanding of the significance of and importance of insects, insectageddon notwithstanding.

I put the blame for lack of entomological funding in the UK on the way that universities have been assessed in the UK over the last twenty years or so (Leather, 2013). The Research Excellence Framework and the way university senior management responded to it has had a significant negative effect on the recruitment of entomologists to academic posts and this has of course meant that entomological teaching and awareness of the importance of insects to global health has decreased correspondingly.

I very much hope that this current outbreak of media hype will go some way to curing the acute case of entomyopia that most non-entomologists suffer from. I fear however, that unless the way we teach biology in primary and secondary schools changes, people will continue to focus on the largely irrelevant charismatic mega-fauna and not the “little things that run the world”

Perhaps if publicly supported conservation organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature concentrated on invertebrates a bit more that would help. A good start would be to remove the panda, an animal that many of us consider ecologically irrelevant from their logo, and replace it with an insect. Unlikely I know, but if they must have a mammal as their flagship species, how about sloths, at least they have some ‘endemic’ insect species associated with them 🙂

References

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P.R. & Dirzo, R. (2017) Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signalled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences, 114, E6089-E6096.

Clark, J.A. & May, R.M. (2002) Taxonomic bias in conservation research. Science, 297, 191-192.

Dirzo, R., Young, H.S., Galetti, M., Ceballos, G., Isaac, N.J.B., & Collen, B. (2014) Defaunation in the anthropocene. Science, 345, 401-406.

Ewald, J., Wheatley, C.J., Aebsicher, N.J., Moreby, S.J., Duffield, S.J., Crick, H.Q.P., & Morecroft, M.B. (2015) Influences of extreme weather, climate and pesticide use on invertebrates in cereal fields over 42 years. Global Change Biology, 21, 3931-3950.

Hallmann, C.A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H., Stenmans, W., Müller, A., Sumser, H., Hörren, T., Goulson, D. & de Kroon, H. (2017) More than 75% decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE. 12 (10):eo185809.

Leather, S.R. (2013) Institutional vertebratism hampers insect conservation generally; not just saproxylic beetle conservation. Animal Conservation, 16, 379-380.

Leather, S.R. & Quicke, D.L.J. (2010) Do shifting baselines in natural history knowledge threaten the environment? Environmentalist, 30, 1-2.

Sánchez-Bayo, F. & Wyckhus, K.A.G. (2019) Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biological Conservation, 232, 8-27.

Shortall, C.R., Moore, A., Smith, E., Hall, M.J., Woiwod, I.P., & Harrington, R. (2009) Long-term changes in the abundance of flying insects. Insect Conservation & Diversity, 2, 251-260.

Well said Simon! I agree with everything you have written. While the press headlines are hysterical, at least they recognise there’s a problem. Sánchez-Bayo & Wyckhus are absolutely right to call attention to it, although I don’t think that we necessarily have to agree with their diagnosis of its probable cause. You are right to call attention to the success of their PR machine, but I say that it’s really good that they approached the press. I agree with you that we entomologists should all be doing more to make the public aware that all is not well in our environment, and that insects are the sentinels who reveal that. Of course, it’s important not to cry wolf, but whatever we think about the detail of this particular story, you are right to say that we now have plenty of evidence that something is seriously wrong, and it needs investigating. Insects are key components of every terrestrial ecosystem, and without them both agriculture and wild nature will be in serious trouble. By contrast, I think that too many entomologists can’t see the wood for the trees, and instead of calling for a prompt follow-up to this evidence, prevaricate about whether the appropriate statistics have been used. We need to act quickly to monitor what is really happening! Unfortunately, collecting evidence of declining insect numbers takes a long time. The less effort is devoted to it, the longer it takes. In my opinion, serious thought needs to be given to the the best way to monitor a relatively large number of sentinel populations, without taking forever to do it. It’s not a sensible option to design the perfect experiment that takes 50 years to do and covers only two or three localities, is it? To me, the Krefeld paper (Hallmann et al, 2017) shows the great power of using data collected by serious non-professional entomologists.The larger the annual volume of data, the fewer years are needed to see a statistically significant trend. So we are going to need large consortia of researchers, probably coordinating the efforts of even greater numbers of local collectors. Of course this isn’t the way that big science is supposed to be done, and the Research Councils prefer three year grant proposals with small teams of professionals. I say that if the Research Councils won’t or can’t cough up the money, then we should look elsewhere. Any ideas?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps we should try and set up something like the long term data continuity trust? We will need some rich donors to get it started though I guess. I wonder if Gates would be interested although he seems keener on killing insects than saving them

LikeLike

Perhaps Mr Gates is indeed already fully committed to existing projects. But you are right to point out that there is potentially a very good PR pay-off for a rich donor to be involved in a high profile ecological monitoring programme. But I think that we should try to get something happening in the UK first. It would help to persuade potential funders if we had a statement of support from relevant national Societies. What about the BES? I would like the RES to have a public position on this too! Let’s see what other readers of this conversation have to say!

LikeLike

There is another less famous but also concerning ecosystem level phenomenon going on, more “super pest” herbivores and predators/parasitoids are proving to be highly invaslve, and there is rapid evolution from a mix of genes being tested against hosts and changing (warming) abiotic conditions. This is driving increased reliance on chemistry as a solution, while insecticide resistance and climate adaptation genes are mixing across populations faster than ever. The pace of this change is phenomenal (we recently reported that 75% ot pest moth eradication programs were in the last 20 years). ” I call it Biogeography at warp speed” – but policy operates much slower than these insects. It is actually global not local jursdictions that need to work on this wicked problem. I suggest you seek funds for international meetings and Fellowships, including OECD Cooperative Research Programme Funds (opens in April). This could cover the economic impacts which are easier to sell.

LikeLike

Pingback: Insectageddon is a great story. But what are the facts? – Ecology is not a dirty word

Excellent blog, Simon! Insects, and invertebrates in general, are overlooked. To the public, it is a case of “out of sight, out of mind”, and they prefer them to be out of sight. For the first 2/3rd of my tenure at UNBC, Invertebrate Zoology was not required for biology majors, which I think says it all. Sadly, I can’t see that anything will change any time soon.

LikeLike

Thanks Staffan. We ca but hope.

LikeLike

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Newsmediaone.com !

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | T I S H

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | BKKNews.org

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Capmocracy.com

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Usworldnewstoday.com

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | SPOT TIMES

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution out of the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Media One

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution to the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion - FreeMedia24

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution to the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Anaptiras.com

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution to the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow | Opinion | Tribunenewslive.com

Pingback: Centrism isn’t the solution to the mess we’re in | Jeff Sparrow – ارم گل

https://theconversation.com/what-happens-to-the-natural-world-if-all-the-insects-disappear-111886

LikeLike

Nice

LikeLike

Kia Ora

I think funding for science with regards to “Insectageddon” is facing the same or similar funding issues science in general faces. There is a degree of political distrust of science and scientists because it cares nothing for political agendas and in the case of earth/environmental sciences very often come contrary to established political positions. But also it is possible that the fear of an an educated populace, who know enough to stand up and openly criticize politicians may be at work. Science in a political context has its uses informing sound policy, discovering cures and new beneficial technology. But it also has its abuses – the arms race; dirty industry andso forth.

LikeLike

Pingback: Insectageddon, Ecological Armageddon, Global insect Apocalypse – why we need sustained long-term funding | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: The Roundabout Review 2019 – navel gazing again | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

The sustainable intensification of agricultural systems offers synergistic opportunities for the co-production of agricultural and natural capital outcomes. Efficiency and substitution are steps towards sustainable intensification, but system redesign is essential to deliver optimum outcomes as ecological and economic conditions change. We show global progress towards sustainable intensification by farms and hectares, using seven sustainable intensification sub-types: integrated pest management, conservation agriculture, integrated crop and biodiversity, pasture and forage, trees, irrigation management and small or patch systems. From 47 sustainable intensification initiatives at scale (each 104 farms or hectares), we estimate 163 million farms (29% of all worldwide) have crossed a redesign threshold, practising forms of sustainable intensification on 453 Mha of agricultural land (9% of worldwide total). Key challenges include investment to integrate more forms of sustainable intensification in farming systems, creating agricultural knowledge economies and establishing policy measures to scale sustainable intensification further. We conclude that sustainable intensification may be approaching a tipping point where it could be transformative.

LikeLike