I have regaled you with tales of green islands twice before, first in relation to trees miraculously surviving mass defoliation events, and second, in terms of leaf miners and their exploitation of cytokinins. This time it is the turn of the cowpat islets to make their appearance. Those of you who are lucky enough to be able to walk in the countryside will probably have noticed that some of the fields you walk through are dotted with lots of clumps of longer grass and perhaps wondered what they are and why they are there.

A recently grazed pasture, showing very clear cowpat islets (Sutton, Staffordshire May 2021).

If you look early enough or carefully later on, you will see that these clumps are associated with cowpats. There have been a lot of theories about why these clumps arise, ranging from increased plant nutrition (Taylor & Rudman, 1966), after all we put manure on our gardens to improve plant growth, to unpalatability of the grass due to raised sugar levels (Plice, 1951). This latter idea has since been dismissed, although the fact that cattle avoid feeding on these clumps has been well documented (Merten & Donker, 1964). There is another explanation for why cattle avoid grazing near cowpats. You may not know it, but despite the fact that cattle don’t seem to have much control (or perhaps they just don’t care) over when and where they deposit their excreta, but cattle, despite the behaviour of bullocks, aren’t stupid. Just like you and me, they aren’t that keen on eating their own and other people’s sh*t. A good reason for avoiding eating excreta, whether your own or someone else’s, is that areas contaminated with dung are associated with higher numbers of gastro-intestinal parasites (Boom & Sheath, 2008; Gethings et al., 2015), so it makes very good sense to avoid eating contaminated grass. Whatever the reason, be it increased nutrition or distastefulness, the result is clumps of longer grass dotted around the pasture taking up between 20 and 30% of the field (Taylor & Rudman, 1966).

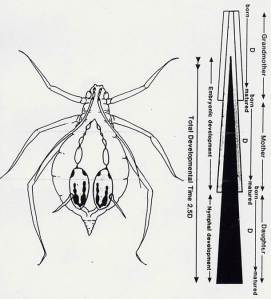

You may, by now, be wondering why an entomologist is going on about cowpats and grass clumps. Well, as you all know, in my world, everything comes round to entomology 🙂 It has been known for some time that hedges and hedgerows provide refuges for insects, admittedly, not all beneficial ones (Lewis, 1969; D’Hulster, M. & Desender, 1982), but nevertheless, an observation that led to the development of beetle banks and conservation headlands (Sotherton et al., 1989; Thomas et al., 1991). It is, however, not just field boundaries that can provide habitats for insects. Belgian coloepterist, the late Konjev Desender and colleagues, found that the sward islets provided extra overwintering sites for staphylinid beetles, which provide an important role in natural pest regulation (D’Hulster & Desender, 1984). Strangely, well to me anyway, interest in the entomological role of sward islets died a death. It wasn’t until almost thirty years later that a former colleague of mine, keen hemipterist Alvin Helden (now at Anglia Ruskin University), and colleagues, found that sward islets were also proving very important refugia for grassland Hemiptera and lycosid and linyphid spiders (Helden et al., 2010: Dittrich & Helden, 2012). Before the grazed sward recovered the islets, which in their study occupied 24% of the pasture, hosted about 50% of the total arthropod community. So a very important role in conserving biodiversity within agroecosystems, but despite this very important finding, sward islet entomology has yet again fallen off the entomological radar 😦

Less recently grazed pasture, but cowpat islets still visible within the recovering sward (Sutton, Staffordshire, May 2021) but still, according to Alvin Helden, containing a higher density of arthropods than the surrounding grazed area (Helden et al., 2010).

I think that revisiting the ecology of sward islets would prove very rewarding for both MSc and PhD projects. Off the top of my head I can come up with a couple of projects; for a PhD, given that the fertilisation level and type affected the relative abundance of two of the Hemipteran families, Delphacids and Cicadellids (Dittrich & Helden, 2012), a comparison of the fauna and flora of sward islets on conventional and organic farms would make a really rewarding project. Harking back to my interests in island biogeography a study of the size, floral composition, structure and distribution of sward islets and how this affects arthropod communities would make a neat MSc project or perhaps even another PhD.

I am sure that with a little bit of thought, many more projects, not just entomological could be devised. Over to you dear readers.

References

Boom, C.J. & Sheath G.W. (2008) Migration of gastrointestinal nematode larvae from cattle faecal pats onto grazable herbage. Veterinary Parasitology, 157, 260-266.

D’Hulster, M. & Desender, K. (1982) Ecological and faunal studies on Coleoptera in agricultural land III. Seasonal abundance and hibernation of Staphylinidae in the grassy edge of a pasture. Pedobiologia, 23, 403–414.

D’Hulster, M. & Desender, K. (1984) Ecological and faunal studies of Coleoptera in agricultural land IV. Hibernation of Staphylinidae in agro-ecosystems. Pedobiologia, 26, 65–73.

Dittrich , A.D.K. & Helden, A.J. (2012) Experimental sward islets: the effect of dung and fertilisation on Hemiptera and Araneae. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 5, 46–56.

Gethings, O.J., Sage, R.B. & Leather, S.R. (2015) Spatio-temporal factors influencing the occurrence of Syngamus trachea within release pens in the south West of England. Veterinary Parasitology, 207, 64-71.

Helden, A.J., Anderson, A., Sheridan, H. & Purvis, G. (2010) The role of grassland sward islets in the distribution of arthropods in cattle pastures. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 3, 291–301.

Lewis, T. (1969) The diversity of the insect fauna in a hedgerow and neighbouring fields. Journal of Applied Ecology, 6, 453-458.

Marten, G.C. & Donker, J.D. (1964) Selective grazing induced by animal excreta. II. Investigation of a causal theory. Journal of Dairy Science, 47, 871-874.

Plice, M. J. (1951) Sugar versus the intuitive choice of foods by livestock. Agronomy Journal, 43, 341-342.

Sotherton, N.W., Boatman, N.D. & Rands, M.R.W. (1989) The ‘conservation headland’ experiment in cereal ecosystems. The Entomologist, 108, 135-143.

Taylor, J.C. & Rudman, J.E. (1966) The distribution of herbage at different heights in ‘grazed’ and ‘dung patch’ areas of a sward under two methods of grazing management. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 66, 29-39.

Thomas, M.B., Wratten, S.D. & Sotherton, N.W. (1991) Creation of ‘island’ habitats in farmland to manipulate populations of beneficial arthropods: Predator densities and emigration. Journal of Applied Ecology, 28, 906-917.