Headline message for those of you too busy to read the whole thing

Aphids have mutualistic symbiotic bacteria living inside them, one set, the primary endosymbionts, Buchnera aphidicola are obligate, i.e. in normal circumstances, the aphid can’t live without them and vice versa. All aphids have them. The others, the secondary symbionts, of which there are, at the last count, more than seven different species, are facultative, i.e. aphids can survive without them and not all aphids have them or the same combination of them. These can help the aphid in many ways, such as, making them more resistant to parasitic wasps, able to survive heat stress better and helping them use their host plants more efficiently. Hosting the secondary symbionts may, however, impose costs on the aphids.

Now read on, or if you have had enough of the story get back to work 🙂

Like us, aphids have a thriving internal ecology, they are inhabited by a number of bacteria or bacteria like organisms. The existence of these fellow travellers and the fact that they are transmitted transovarially, has been known for over a hundred years (Huxley, 1858; Peklo, 1912)*, although their role within the body of the aphids was not entirely understood for some time, despite Peklo’s conviction that they were symbionts and transferred via the eggs to the next generation. Some years later the Hungarian entomologist László Tóth** hypothesised that aphids because the plant sap that they feed on did not contain enough proteins to meet their demands for growth, must be obtaining the extra nitrogen they needed from their symbionts, although he was unable to prove this empirically (Tóth, 1940). This was very firmly disputed by Tom Mittler some years later, who using the giant willow aphid, Tuberolachnus salignus, showed that aphid honeydew and willow phloem sap contained the same amino acids (Mittler, 1953, 1958ab). It was not only aphidologists who were arguing about the nature and role of insect symbionts, as this extract from a review of the time makes clear,

“It is not our purpose here to harangue on terminology; suffice it to say that we will use “symbiote” for the microorganism and “host” for the larger organism (insect) involved in a mutualistic or seemingly mutualistic association.” (Richards & Brooks, 1958).

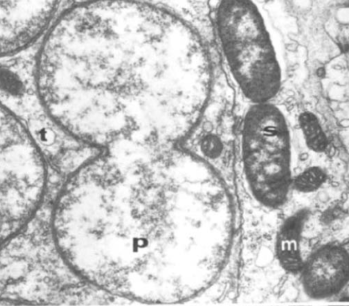

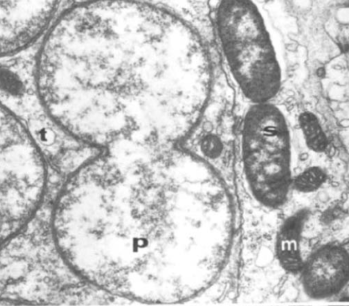

Interestingly it is in this paper that they mention, using the term “provocactive” the use of antibiotics to create aposymbiotic individuals in attempts to prove that the symbionts were first bacteria, and second, benefiting their insect hosts. The concluded that there was enough evidence to suggest that the endosymbionts were involved in some way in the nutritional and possibly reproductive processes of the insects studied, mainly cockroaches. At the time of the review no similar work had been done on aphids. A few years later though, two American entomologists sprayed aphids with several different antibiotics and found that this caused increased mortality and reduced fecundity when compared with untreated ones (Harries & Mattson, 1963). Presaging its future dominance in aphid symbiont work, one of the aphids was the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Antibiotics were also shown to eliminate and damage the symbionts associated with Aphis fabae followed by impaired development and fecundity in the aphid itself adding yet more evidence that the symbionts were an essential part of the aphid biome (Ehrhardt & Schmutterer, 1966). There was, however, still much debate as to how the symbionts provided proteins to the aphids, and although light and electron microscopy studies confirmed that the symbionts were definitely micro-organisms (Lamb & Hinde, 1967; Hinde, 1971), the answer to that question was to remain unanswered until the 1980s although the development of aphid artificial diets (Dadd & Krieger, 1967) which could be used in conjunction with antibiotic treatments, meant that it was possible to show that the symbionts provided the aphids with essential amino acids (Dadd & Kreiger, 1968; Mittler, 1971ab).*** Although the existence of secondary symbionts in other Homoptera was known (Buchner, 1965), it was not until Rosalind Hinde described them from the rose aphid, Macrosiphum rosae, that their presence in aphids was confirmed (Hinde, 1971). Of course it was inevitable that they would then be discovered in the pea aphid although their role was unknown (Grifiths & Beck, 1973). Shortly afterwards they were able to show that material produced from the symbionts was passed into the body of the aphid (Griffiths & Beck, 1975) and it was also suggested suggested that it was possible that the primary symbionts were able to synthesise amino acids (Srivastava & Auclair, 1975) and sterols (Houk et al., 1976) for the benefit of their aphid hosts (partners). By the early 1980s it was accepted dogma that aphids were unable to reproduce or survive without their primary symbionts (Houk & Griffiths, 1980; Ishikawa, 1982) and by the late 1980s that dietary sterols were provided by the primary symbionts (Douglas, 1988).

Primary symbiont (P) in process of dividing seen next to secondary symbionts (S) and mitochondrion (m) from Houk & Griffiths (1980).

Despite the huge amount of research and the general acceptance that the endosymbionts were an integral part of the aphid’s biome “The mycetocyte symbionts are transmitted directly from one insect generation to the next through the female. There are no known cases of insects that acquire mycetocyte symbionts from the environment or from insects other than their parents” (Douglas , 1989), their putative identity was not determined until 1991 (Munson et al., 1991), when they were named Buchnera aphidicola, and incidentally placed in a brand new genus. Note however, that like some aphids, B. aphidicola represents a complex of closely related bacteria and not a single species (Moran & Baumann, 1994). Research on the role of the primary symbionts now picked up pace and it was soon confirmed that they were responsible for the synthesis of essential amino acids used by the aphids, such as tryptophan (Sasaki et al., 1991; Douglas & Prosser, 1992) and that it was definitely an obligate relationship on both sides**** (Moran & Baumann, 1994).

Now that the mystery of the obligate primary endosymbionts was ‘solved’, attention turned to the presumably facultative secondary symbionts, first noticed more than twenty years earlier (Hinde, 1971)***** began to be scrutinised in earnest. Nancy Moran and colleagues (Moran et al., 2005) identified three ‘species’ of secondary bacterial symbionts, Serratia symbiotica, Hamiltonella defensa and Regiella insecticola. As these are not found in all individuals of a species they are facultative rather than obligate. The secondary symbionts were soon shown not to have nutritional benefits for the aphids (Douglas et al., 2006). They are instead linked to a whole swathe of aphid life history attributes, ranging from resistance to parasitoids (Oliver et al., 2003; 2005; Schmid et al., 2012), resistance to heat and other abiotic stressors (Montllor et al., 2002; Russell & Moran 2006; Enders & Miller, 2016) and to host plant use (Tsuchida et al., 2004; McLean et al., 2011; Zytynska et al., 2016).

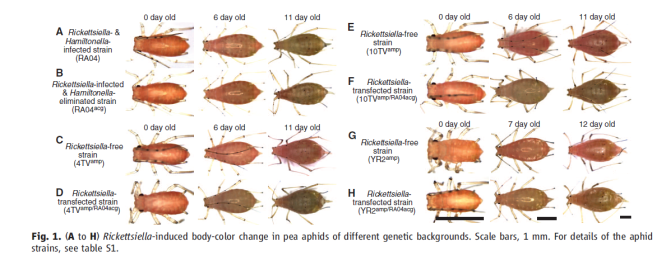

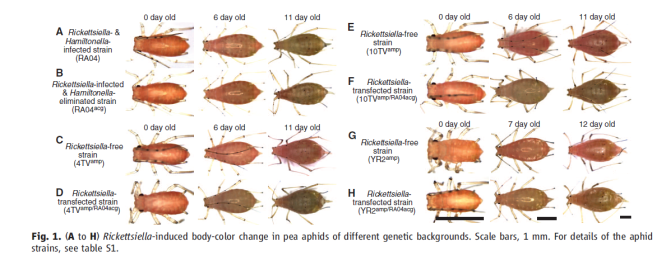

And finally, Mittler (1971b) mentions the reddish colouration developed by aphids reared on some of the antibiotic diets and hypothesises that this may be linked to the symbionts. I have written earlier about aphid colour variants and the possibility that the symbionts may have something to do with it. The grain aphid, Sitobion avenae has a number of colour variants and it was suggested that levels of carotenoids present might have something to do with the colours expressed and that in some way this was controlled by the presence of absence of symbionts (Jenkins et al., 1999). More recently Tsuchida and colleagues in a series of elegant experiments on the ubiquitous pea aphid, have shown that the intensity of green colouration is dependent on the presence of yet another endosymbiont, a Rickettsiella (Tsuchida et al., 2010). The authors hypothesise that being green

Elegant demonstration that in some strains of the pea aphid, green colour is a sign of an infection by Rickettsiella (Tsuchida et al., 2010).

rather than pink or red, may reduce predation by ladybirds as has been suggested before (Losey et al., 1997).

New secondary symbionts continue to be discovered and with each discovery, new hypotheses are raised and tested. It would seem that there is a whole ecology of secondary symbionts within the aphid biome waiting to be explored and written about (Zytynska & Weisser, 2016). What are you waiting for, but do remember to come up for air sometime and relate what you find back to the ecology of the aphids 🙂

References

Buchner, P. (1965) Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms. Interscience, New York.

Dadd, R.H. & Krieger, D.L. (1967) Continuous rearing of aphids of the Aphis fabae complex on sterile synthetic diet. Journal of Economic Entomology, 60, 1512-1514.

Dadd, R.H. & Krieger, D.L. (1968) Dietary amino acid requirements of the aphid Myzus persicae. Journal of Insect Physiology, 14, 741-764.

Douglas, A.E. (1988) On the source of sterols in the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, reared on holidic diets. Journal of Insect Physiology, 34, 403-408.

Douglas, A.E. (1998) Mycetocyte symbiosis in insects. Biological Reviews, 64, 409-434.

Douglas, A.E. & Prosser, W.A. (1992) Sythesis of the essential amiono acid trypthotan in the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) symbiosis. Journal of Insect Physiology, 38, 565-568.

Douglas, A.E., Francois, C.M.L.J. & Minto, L.B. (2006) Facultative ‘secondary’ bacterial symbionts and the nutrition of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Physiological Entomology, 31, 262-269.

Ehrhardt, P. & Schmutterer, H. (1966) Die Wirkung Verschiedener Antibiotica auf Entwicklung und Symbionten Künstlich Ernährter Bohnenblattläuse (Aphis fabae Scop.). Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Ökologie der Tiere, 56, 1-20.

Enders, L.S. & Miller, N.J. (2016)Stress-induced changes in abundance differ among obligate and facultative endosymbionts of the soybean aphid. Ecology & Evolution, 6, 818-829.

Griffiths, G.W. & Beck, S.D. (1973) Intracellular symbiotes of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Journal of Insect Physiology, 19, 75-84.

Griffiths, G.W. & Beck, S.D. (1975) Ultrastructure of pea aphid mycetocystes: evidence for symbiote secretion. Cell & Tissue Research, 159, 351-367.

Harries, F.H. & Mattson, V.J. (1963) Effects of some antibiotics on three aphid species. Journal of Economic Entomology, 56, 412-414.

Hinde, R. (1971) The control of the mycetome symbiotes of the aphids Brevicoryne brassicae, Myzus persicae, and Macrosiphum rosae. Journal of Insect Physiology, 17, 1791-1800.

Houk, E.J. & Griffiths, G.W. (1980) Intracellular symbiotes of the Homoptera. Annual Review of Entomology, 25, 161-187.

Houk, E.J., Griffiths, G.W. & Beck, S.D. (1976) Lipid metabolism in the symbiotes of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology, 54B, 427-431.

Huxley, T.H. (1858) On the agamic reproduction and morphology of Aphis – Part I. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, 22, 193-219.

Ishikawa, H. (1978) Intracellular symbionts as a major source of the ribosomal RNAs in the aphid mycetocytes. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications, 81, 993-999.

Ishikawa, H. (1982) Isolation of the intracellular symbionts and partial characterizations of their RNA species of the elder aphid, Acyrthosiphon magnoliae. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology, 72B, 239-247.

Jenkins, R.L., Loxdale, H.D., Brookes, C.P. & Dixon, A.F.G. (1999) The major carotenoid pigments of the grain aphid Sitobion avenae (F.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Physiological Entomology, 24, 171-178. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-3032.1999.00128.x/pdf

Lamb, R.J. & Hinde, R. (1967) Structure and development of the mycetome in the cabbage aphid, Brevicoryne brassciae. Journal of invertebrate Pathology, 9, 3-11.

Losey, J. E., Ives, A. R., Harmon, J., Ballantyne, F. &Brown, C. (1997). A polymorphism maintained by opposite patterns of parasitism and predation. Nature, 388, 269-272.

McLean, A.H.C., van Asch, M., Ferrari, J. & Godfray, H.C.J. (2011) Effects of bacterial secondary symbionts on host plant use in pea aphids. Proceedings of the Royal Society B., 278, 760-766.

Mittler, T.E. (1953) Amino-acids in phloem sap and their excretion by aphids. Nature, 172, 207.

Mittler, T.E. (1958a) Studies on the feeding and nutrition of Tuberolachnus salignus (Gmelin) (Homoptera, Aphididae). II. The nitrogen and sugar composition of ingested phloem sap and excreted honeydew. Journal of Experimental Biology, 35, 74-84.

Mittler, T.E. (1958b) Studies on the feeding and nutrition of Tuberolachnus salignus (Gmelin) (Homoptera, Aphididae). III The nitrogen economy. Journal of Experimental Biology, 35, 626-638.

Mittler, T.E. (1971a) Dietary amino acid requirements of the aphid Myzus persicae affected by antibiotic uptake. Journal of Nutrition, 101, 1023-1028.

Mittler, T.E. (1971b) Some effects on the aphid Myzus persicae of ingesting antibiotics incorporated into artificial diets. Journal of Insect Physiology, 17, 1333-1347.

Montllor, C.B., Maxmen, A. & Purcell, A.H. (2002) Facultative bacterial endosymbionts benefit pea pahids Acyrthosiphon pisum under heat stress. Ecological Entomology, 27, 189-195.

Moran, N. & Baumann, P. (1994) Phylogenetics of cytoplasmically inherited microrganisms of arthropods. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 9, 15-20.

Moran, N.A., Russell, J.A., Koga, R. & Fukatsu, T. (2005) Evolutionary relationships of three new species of Enterobacteriaceae living as symbionts of aphids and other insects. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 71, 3302-3310.

Munson, M.A., Baumann, P. & Kinsey, M.G. (1991) Buchnera gen. nov. and Buchnera aphidicola sp. Nov., a taxon consisting of the mycetocyte-associated, primary endosymbionts of aphids. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 41, 566-568.

Oliver, K.M., Russell, J.A., Moran, N.A. & Hunter, M.S. (2003) Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 100, 1803-1807.

Oliver, K.M., Moran, N.A. & Hunter, M.S. (2005) Variation in resistance to parasitism in aphids is due to symbionts not host genotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 102, 12795-12800.

Peklo, J (1912) Über symbiotische Bakterien der Aphiden. Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft, 30, 416-419.

Richards, A.G. & Brooks, M.A. (1958) Internal symbiosis in insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 3, 37-56.

Russell, J.A. & Moran, N.A. (2006) Costs and benefits of symbiont infection in aphids: variation among symbionts and across temperatures. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 273, 603-610.

Sasaki, T., Hayashi, H. & Ishikawa, H. (1991) Growth and reproduction of the symbiotic and aposymbiotic pea aphids, Acyrthosiphon pisum mainatained on artificial diets. Journal of Insect Physiology, 37, 749-756.

Schmid, M., Sieber, R., Zimmermann, Y.S. & Vorburger, C. (2012) Development, specificity and sublethal effects of symbiont-conferred resistance to parasitoids in aphids. Functional Ecology, 26, 207-215.

Srivastava P.N. & Auclair, J.L. (1975) Role of single amino acids in phagostimualtion, growth, and survival of Acyrthosiphon pisum. Journal of Insect Physiology, 21, 1865-1871.

Tóth, L. (1940) The protein metabolism of aphids. Annales Musei Nationalis Hungarici 33, 167-171.

Tsuchida, T., Koga, R. & Fukatsu, T. (2004) Host plant specialization governed by facultative symbiont. Science, 303, 1989.

Tsuchida, T., Koga, R., Horikawa, M., Tsunoda, T., Maoka, T., Matsumoto, S., Simon, J. C. &Fukatsu, T. (2010). Symbiotic bacterium modifies aphid body color. Science 330: 1102-1104.

Zytynska, S. E. &Weisser, W. W. (2016). The natural occurrence of secondary bacterial symbionts in aphids. Ecological Entomology, 41, 13-26.

Zytynska, S.E., Meyer, S.T., Sturm, S., Ullmann, W., Mehrparvar, M. & Weisser, W.W. (2016) Secondary bacterial symbiont community in aphids responds to plant diversity. Oecologia, 180, 735-747.

Footnotes

Peklo, J. (1953) Microorganisms or mitochondria? Science, 118, 202-206.

Buchnera appears to have been ‘lost’ but replaced by a yeast like symbiont (Braendle et al., (2003).

Braendle, C., Miura, T., Bickel, R., Shingleton, A.W., Kambhampari, S. & Stern, D.L. (2003) Developmental origin and evolution of bacteriocytes in the aphid-Buchnera symbiosis. PloS Biology, 1, e21. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000021.